If tradition places the early seat of the Armenian Church at the sanctuary of Edchmiadzin, in Vagharshabad, it also accepts that the first heads of this Church, those from the family of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, may have resided at the sanctuary of Ashdishad (n° 57) in the Taronid. Though their residence may have been indeterminate at first, it was subsequently established in different places following political whims, and among others at Twin (=Dwin), Ani, Aght‘amar (n° 17), as well as Hromgla [Rumkale], on the Euphrates not far from Edessa/Etesia [Urfa]. In the second half of the 13th century, the conflict with Aght‘amar being still unresolved, the catholicos of Armenia resided in the Hromgla fortress, under the protection of the Pahlavid (Bhalavuni) princes. When the Mamaluks occupied Hromgla in 1292 the Church was forced to transfer its headquarters to Sis [Kozan, 37°26' N, 35°48' E], capital of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia.

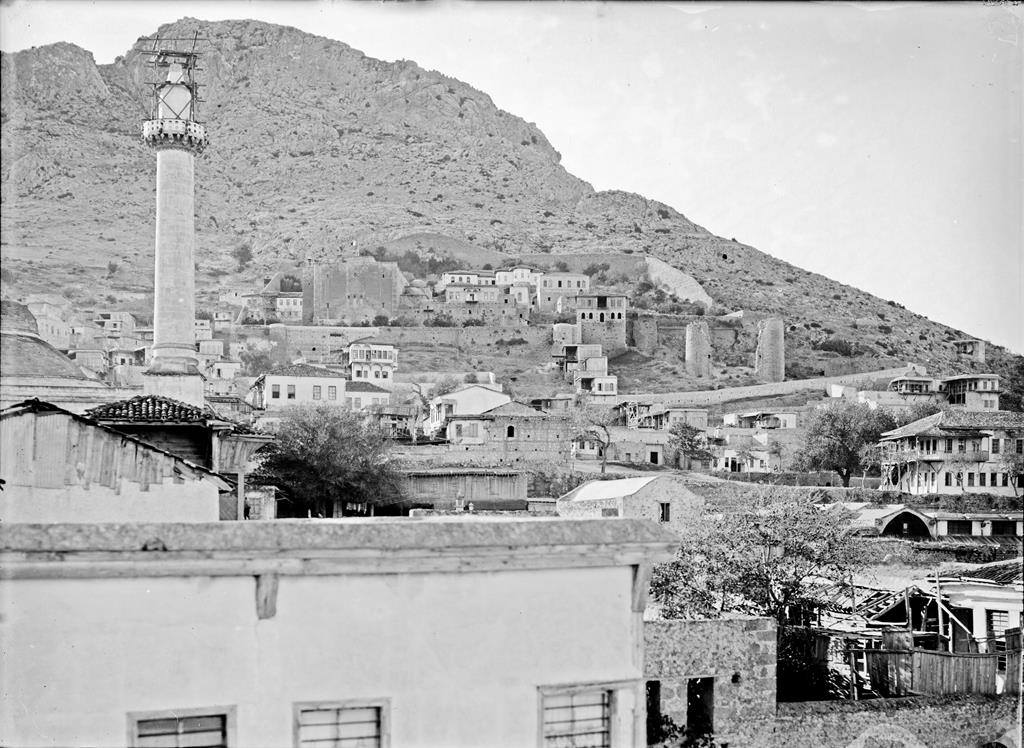

Siège catholicossal, vue générale nord-est (©Bibliothèque orientale de l'USJ).

We know that, in 1226, King Het‘um I built the domed church of Holy Wisdom (Surp Sop‘ia) in Sis, at the foot of the fortress and no doubt even within the walls of his palace. But this is not necessarily in this place, or in the church of Holy Edchmiadzin, built in 1197 by the future Leon I, that the catholicos established themselves when they moved to Sis. There, too, in 1423, Paul II of Karni (Boghos Karnetsi, 1419-1428), either built or renovated a convent dedicated to Saint Anne, placed under the protection of the right hand of the Illuminator. This was the Old Convent, which served as the residence of the catholicos before Holy Wisdom was made a patriarchal church. The fall of Sis and the end of the monarchy, in 1375, which some of the local seigneurs nevertheless survived, forced the catholicosate to deal with its successors, the Turkmen emirates, which were vassals of Egypt. Sis in particular fell to the Ramadanids. Catholicos Theodore II of Cilicia (T‘éotoros Guiliguetsi, 1382-1392) was poisoned, following a plot involving most certainly the Latinophile Armenians, by Emir Ömer, who also had a large number of dignitaries executed. In 1401, Sis was ravaged by Tamerlane and probably returned to the Armenians before being ceded to the Ramadanids in 1404. At this time of political instability also marked by opposition within the Church itself between traditionalist and Latinophile movements, several catholicos would meet a tragic death. In the second quarter of the 15th century, the patriarchal throne was occupied by Gregory IX Mussabeguiants (Krikor Mussabeguiants, 1439-1442). It was under his reign that, at the instigation of the Eastern doctors of the Armenian Church led by Thomas of Medzop‘ (T‘ovmas Medzop‘etsi, † 1447, see n° 9), an impromptu synod called in 1441 decided to transfer the seat of the Armenian Church from Sis to Edchmiadzin.

This decision, in which Gregory IX did not participate and with which, like a large part of his Church, he did not agree, led its authors, after the catholicos’ refusal to leave Sis, to elect a new catholicos at Edchmiazdin, in the person of a disciple of the Artzwaper school (n° 7), the monk Cyriacus of Khor Virab (Guiragos Virabetsi). Cyriacus’ decision to lift the anathema on Aght‘amar (see n° 17), but more generally his reputation for probity, won him esteem. Yet his destitution in 1443, brought about by the machinations of part of the Eastern clergy for whom he had lost his usefulness, and his replacement with Gregory X of Magu (Krikor Magwetsi, 1443-1466) in the new see of Edchmiadzin, sealed the divide. In 1444 the doctors of the Western branch of the Church, denouncing an usurpation, provided Gregory IX with a successor by elevating the Bishop of Eudocias [Tokat], Garabed (Garabed Evtoguiatsi, 1444-1477, see n° 72), to the dignity of patriarch of Sis. Garabed of Eudocias inaugurated a new line of catholicos at Sis, which were customarily named in a specific order: the second to carry the name, Garabed of Eudocias, thus became Garabed I of Cilicia, or of Sis. The catholicos who remained at Sis long continued to claim the title “Catholicos of All Armenians” (amenayn Hayots), a title that would be appropriated by the incumbents of the new see of Edchmiadzin, but would also at times be claimed by the catholicos of Aght‘amar.

Quartier du catholicossat, vue est (Archives départementales de l’Eure, 36 Fi 819, fonds Gabriel Bretocq 1918-1922).

Garabed I took up residence in Sis at the convent of Saint Anne. His pontificate was marked by two major events: in 1461 the population of Sis rose up against another emir Ömer, and the patriarchal convent was looted; while in 1468 Sis was taken by the insurgent emir of Marash [Maraş], the Dulkadir Shah Suvar, who settled the town with Syrian Muslims. In the previous year the emir had already taken over the fortress of Vahga [Feke], the secondary residence of the catholicos of Sis, where their presence would once again be attested until the 18th century. Garabed I was a contemporary of the two great catholicos of Aght‘amar, Zacharias III and Stephen IV, who would unite the sees of Aght‘amar and Edchmiadzin under their authority in 1460 and in 1467 but were unable to bring Sis into line. Garabed’s successors would in turn defend the legitimacy of their seat, which had authority over all Armenians living in the territories of Egypt, Caramania – which ceased to exist in 1475 – and the Ottoman Empire, with, on one side Jerusalem, the seat of an Armenian patriarchate founded after the Arab conquest and, on the other side, Constantinople, which would soon be the site of a second patriarchate. The Ottoman conquest of Cilicia, like those of the western part of Greater Armenia, Syria and Egypt, occurred under the catholicosate of John II of T‘lguran (Hovhannes T‘lgurantsi, 1489-1525). An erroneous tradition identifies him as a poet to whom were attributed some fifteen pieces contained in a song collection published in 1513 in Venice – one of the first five Armenian books to have been printed – and a version of the Song of Libarid, which relates the exploits and death of this Royal Marshal of the kingdom killed in 1369 before the walls of Sis. However these works were in fact written by a 14th- or 15th-century author of the same name. Alternatively, John II was an active patriarch, who, with the help of Issa rais, had a new patriarchal residence built in Aleppo, which was less exposed than that at Sis. Other projects, conducted under the authority of the patriarchs of Jerusalem, some of which were entrusted to Gregory of Darôn (Krikor Darôntsi) and his disciple Malachia of Terjan [Tercan] (Maghak‘ia Terjantsi) (see n° 44, 45, 46, 56), were undertaken in Jerusalem, where the catholicos was striving to put the finances of the congregation of Saint James in order, while an edict confirming the Patriarchate, delivered in 1517 by Selim I, consolidated the Armenian presence in the city.

Faced with the arbitrary conduct of the Turkmen chiefs and the devastation spread by the Jelali companies, which wrecked havoc throughout Asia Minor at the turn of the 17th century, the incumbents of the see of Sis also had to counter the ambitions of several anti-catholicos and to ensure the loyalty of Jerusalem and Constantinople, whose affairs they were called upon to manage on several occasions. Furthermore they exercised their ministry against a backdrop of repeated solicitations from Rome, resolutely renewed, with the Propagation of the Faith, by popes Gregory XIII and Gregory XV, as well the diocesan war between Sis and Edchmiadzin. We often find them living in Aleppo. If the austere and humble ways of Kachadur I Chorig (1550/1-1560) would long be the subject of popular tales, Azaria I of Julfa (Azaria Dchughayetsi, 1581-1601) and John IV of Aïntab (Hovhannes Aynt‘abtsi, 1602-1621) stood out for their nuanced relations with Rome as well as for their repeated interventions designed to relieve the patriarchal convent of Jerusalem of the crushing debt caused by increased taxation or by the obligation to periodically renew its rights. They also encouraged construction and renovation. In Sis, the church of Holy Wisdom became a patriarchal church, and a “royal” church of the Holy Savior (Surp P’rguich) was associated with it. In 1587 the town was reported to have had twelve other churches and chapels. Sis also carried on a rich tradition of sacred song and chant notation. In the 17th century its school continued to be reputed for its “neumes”, just as the Moush [Muş] school – an allusion to the monastery of Saint John (n° 56) – was known for its “Psalms”.

Simeon II of Sebastia [Sivas] (Simeon Sepasdatsi, 1633-1648) was a staunch defender of the legitimacy, and even the supremacy, of the see of Sis, as is shown by his correspondence with Philip I of Aghpag (P‘ilibbos Aghpaguetsi, 1633-1655, see n° 34), the incumbent catholicos of Edchmiadzin. The two sees exercised their authority over a territory now divided between the Persian and Ottoman empires, each of which occasionally lent them support. In 1638 Simeon II sent a letter of conciliation to Edchmiadzin. But it was not until the great assembly of Jerusalem in 1652, at which Patriarch Asdwadzadur III of Darôn (Asdwadzadur Darôntsi) received both catholicos – Philippe I, incumbent of the see of Edchmiadzin, and Nerses I of Sebastia (Nerses Sepasdatsi, 1648-1654) the new titular catholicos of Sis – that an agreement was reached on the allocation of diocese and the appointment of bishops. One of the outcomes of this agreement would nevertheless be the aggravation of the conflict between Edchmiadzin and the catholicosate of Aght‘amar (see n° 17). In the second half of the 17th century, tension shifted to the activity of the Latinophile circles, which were attempting to bring not only the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople under their influence but also the see of Sis. Catholicos Theodore II of Sebastia (T‘oros Sepasdatsi, 1654-1657) spent 1656-1657 in Constantinople trying to counter their initiatives. But Khachadur III of Galatia (Khachadur Kaghadiatsi, 1657-1674), who was on their side, managed to succeed him in Sis, thereby favoring the dissidence of part of the clergy and the faithful. In the long conflict that had just begun, several catholicos, forced to abdicate or renounce their faith, would flee to Rome.

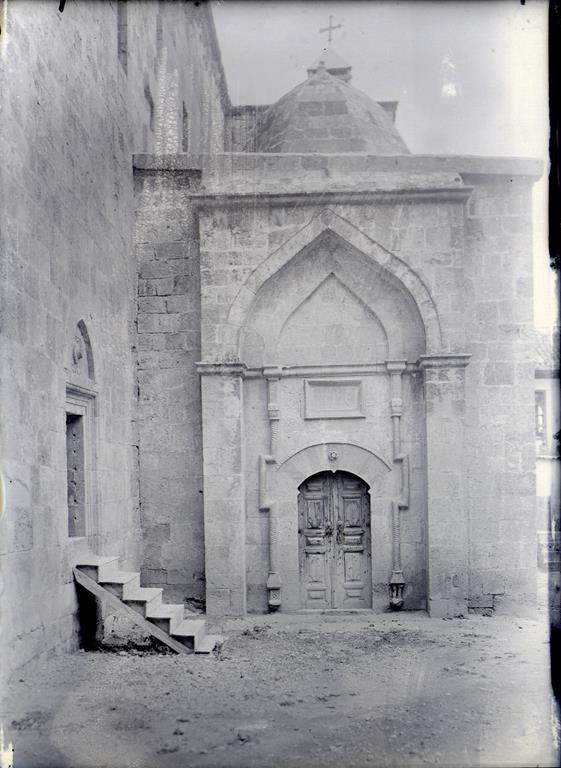

La chapelle Saint-Édchmiadzin, façade ouest (Archives départementales de l’Eure, 36 Fi 825, fonds Gabriel Bretocq 1918-1922).

It was John V of Hajën (Hovhannes Hajëntsi, 1705-1721) who undertook to restore the seat of Sis, though not without having been obliged to share his function with Peter II of Berea [Aleppo] (Bedros Periatsi, 1708-1710) for a few years, during which time he moved to the monastery of Saint James of Hajën (n° 96). It was to this monastery that John VI of Hajën, installed in 1729, would be obliged to withdraw after Mahmoud I granted the Achabahian family of Sis, custodians of the right hand of the Illuminator, the privilege of filling the office of catholicos. Between 1733 and 1865, this family would provide the throne of Sis with an unbroken line of catholicos. Their accession took place in difficult circumstances marked by both opposition from Edchmiadzin and intrigues among the Latinophiles, in addition to violence and rivalry on the part of the Turkmen chiefs: the Divanoghlu established in the region of Sis and the Khozanoglu, around Vahga. The first three Achabians, all brothers, would be assassinated in 1737, 1758 and 1770, respectively. Luke I (Ghugas Achabahian, 1733-1737), consecrated at Vagha by his predecessor, reinvigorated the patriarchal school, which would become the University Saint Nerses of Lampron. He renovated the church of the Holy Mother of God and the other buildings of the convent of Saint Anne. In 1741, Mickael I (Mik‘ayel Achabahian, 1737-1758) was forced to have recourse to imperial firman to wrest from the catholic dissidents the church they had appropriated in Aleppo; but he was unable to oppose the creation of an Armenian catholic patriarchate, in 1739, which was established on Mount Lebanon in 1749. Hostage to inter-tribal feuding, Gabriel I (Kapriel Achabahian, 1758-1770) was murdered by the Khozanoghlu, which several sources also credit with the death of his two successors, the scholar Ephraim I (Ep‘rem Adchabahian, 1771-1784) and Theodore III (T‘eotoros Achabahian, 1784-1796).

It was on the initiative of Theodore III, whose investiture was held in Constantinople in the presence of the nuncio to Edchmiadzin, that the right hand of Gregory the Illuminator, which had been kept in Sis in the home of the Achabahians since the 15th century, was reunited with the relics in the patriarchal convent, thereby conferring new dignity on the occupants of the seat of Sis. They now held the title of “Catholicos of All Armenians, patriarchs of the House of Cilicia and servants of the right hand of the Illuminator”. The Achabahians’ work would nevertheless attain its full dimension only with Cyriacus I the Great (Guiragos Achabahian, 1797-1822), who established the patriarchal convent on the slopes of the Sis fortress on the steep site of the former royal residence. The New Convent, which excluded part of the remains of the original constructions and was surrounded by a wall, was built between 1797 and 1810 around the church of Holy Wisdom, which had been entirely remodeled and given several chapels and a bell tower. Although it had been authorized and despite its deliberately compact architecture, Cyriacus I received for his initiative a death sentence that would be lifted definitively only after his interview with Mahmud II in 1820. He would nonetheless be poisoned to death by the Khozanoghlu in 1822. His successors were unable to continue the recovery, and would see their efforts doomed time and again by exactions and violence on the part of the Turkmen tribes, which repeatedly forced them to abandon Sis for Adana or other parts. Mickael II (Mik‘ayel Achabahian, 1832-1855) would face further opposition from the religious council of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which tried to force him to seek their permission to appoint bishops. The reign of the last of the Achabahians, Cyriacus II (Guiragos, 1855-1865), was contemporaneous with the promulgation, in 1860-1863, of the Armenian National Constitution in the Ottoman Empire, which considerably strengthened the attributions and prerogatives of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. Cyriacus II temporarily revived the catholicosal school, which had fallen into decline, but more important, he convinced the imperial powers to send an army to bring to heel the Khozanoghlu and other beys who were encamped in the mountains.

The provisions of the National Constitution concerning the administration of diocese and the powers granted the Patriarchate of Constantinople inevitably sparked power struggle with the catholicosates of Aght‘amar and Sis. The attempt on the part of an Achabahian nephew, at the time bishop of Aleppo, to occupy the throne of Sis in 1866 under the name of Cyriacus III was thwarted when the patriarchate intervened and had him sent to Constantinople by the authorities before exiling him until 1876 to the Armash monastery (n° 78). Elected catholicos in the meantime, Mgrdich I Kefsizian (1871-1894) would nevertheless fight the implementation of the constitutional provisions within his jurisdiction as well as the planned demotion of his seat to the rank of prelacy, whereas at the same time, the Catholicosate of Edchmiadzin, now in Russian territory, declared Sis to be illegitimate, in violation of the agreement reached in 1652. His position was based in particular on the synod he called in 1880 in Sis, the resolutions of which he would defend in Constantinople until 1881, without ever coming to an agreement with the patriarchate. The material situation of the patriarchal convent in Sis continued to decline, even though a belated end had been put to the beys’ extortions, the catholicos having concentrated his efforts on Marash [Maraş], Aïntab [Gaziantep] where he founded a school, and Aleppo.

After the death of Mgrdich I Kefsizian, the demands of the imperial government and those of the patriarchate would make it impossible to fill the seat of Sis until 1902. Sahag II Khabayan († 1939), the last catholicos to reside in Sis and a man of exceptional stature, would distinguish himself both by his conciliatory attitude with regard to Edchmiadzin – where Mgrdich I Khrimian, the “Little Father” of the people (see nos 1 and 53) occupied the seat – which he accepted to consider as a supreme seat, and by his firm stance with regard to Constantinople on the question of appointments. Courageously, he attempted to relieve the misery of the Sis convent and to maintain a seminary there, which he was nevertheless forced to close on two occasions, in 1903 and 1909. In prelude to the 1915 genocide, the massacres instigated by the Young Turks of the Committee of Union and Progress in 1909, in power since the previous year, left a bloody trail throughout Cilicia. With the support of the Armenian authorities in Constantinople, Sahag II worked ceaselessly to rebuild the ruins, and to set up orphanages, schools and factories. This momentum would be interrupted first by the Great War and then by the Great Crime (Medz Eghern) – the Armenian genocide. Placed under house arrest in Jerusalem and then in Damascus, forced in 1916 to accept the title of Catholicos-Patriarch of the Armenians of Turkey, attributed to him by the government when it abolished the National Constitution, ordered the fusion of the catholicosates of Sis and Aght‘amar and brought the patriarchates of Constantinople and Jerusalem under the authority of the new creation, Sahag II was forced to witness the deportation and extermination of his people. Perhaps his continued relations with Jemal Pacha, Minister of the Navy and Chief of the 4th Ottoman Army, had something to do with the latter’s decision to spare the lives of certain deportees in Syria and Palestine; but his attitude can also be explained by his disagreement with the radical branch of the Committee of Union and Progress and by the secret negotiations he was conducting with the Entente Powers. At the end of the war, Sahag II joined the survivors in Cilicia, where the French forces were established. But with the reversal of French diplomatic policy, which led to the signature of the Angora [Ankara] agreement with the Kemalists in October 1921, Cilicia was evacuated. The Kemalists were rightly seen as the successors of the Young Turks, and the returned deportees were once again forced into exile. In July 1920, the Armenian population of Sis was evacuated to Adana, while the populations of Hajën [Sayimbeyli] (see n° 96) and other towns were abandoned to their fate. Sahag II left Adana definitively in December 1921 to join the surviving Armenian refugees in Cyprus and the Syro-Lebanese territories under French mandate

Burdened with a long history and an unshakable witness to a succession of tragedies, Sahag II, now catholicos of the “Great House of Cilicia”, would work with his coadjutor, Papguen II (Papguen I Gulesserian, 1931-1936), to revive the institution of the catholicosate of Sis, which he finally managed to establish in Lebanon, at Antelias, and to which the dioceses of the Pariarchate of Jerusalem would be transferred.

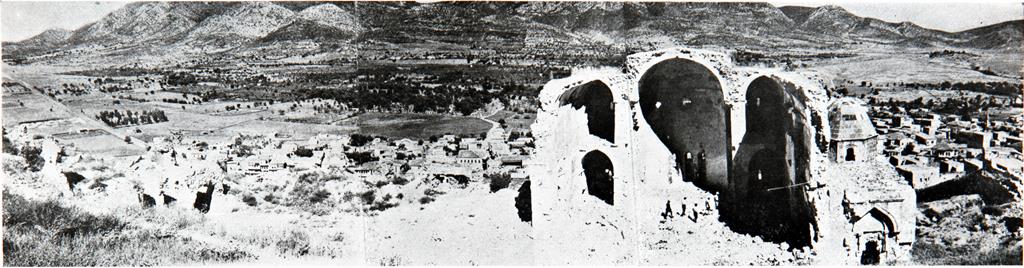

Vue générale ouest : bloc absidial de l'église Sainte-Sophie avec la chapelle Saint-Édchmiadzin, 1943 (Kéléchian, 1949, 749).

The buildings of the catholicosate of Sis included:

In the Old Convent located southwest of the town:

• The church of Saint Anne or of the Holy Mother of God, with a dome probably built in 1423 and restored in 1734; the porch held the tombs of the earliest catholicos and of several prelates.

• Outbuildings, in which a school had been set up in the 19th century.

In the New Convent:

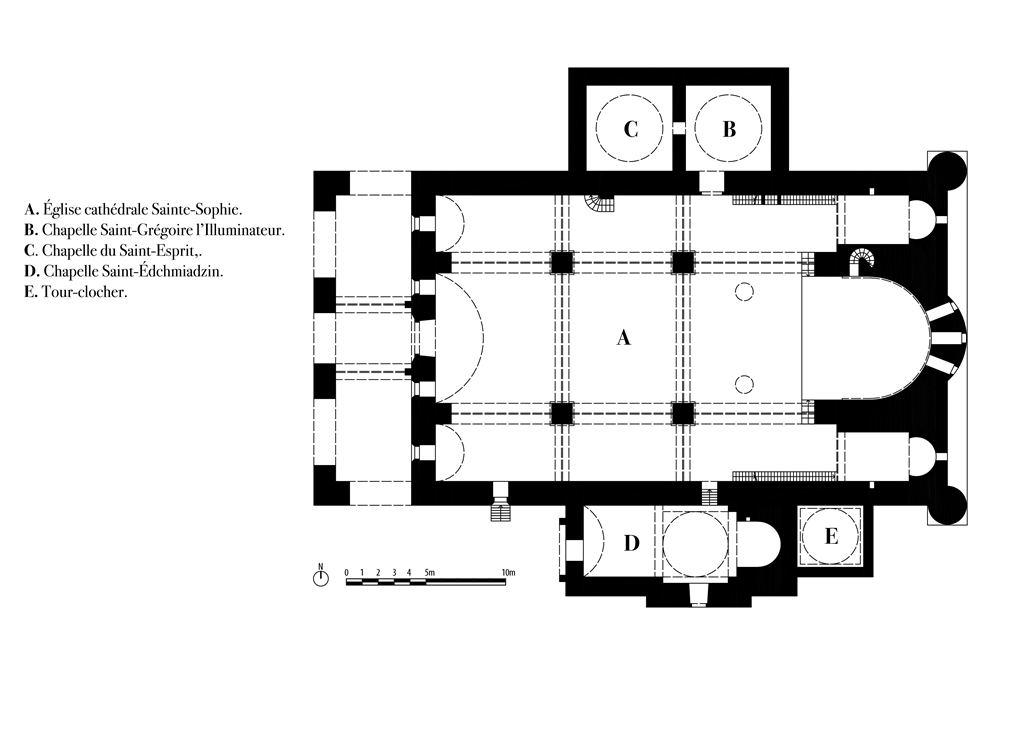

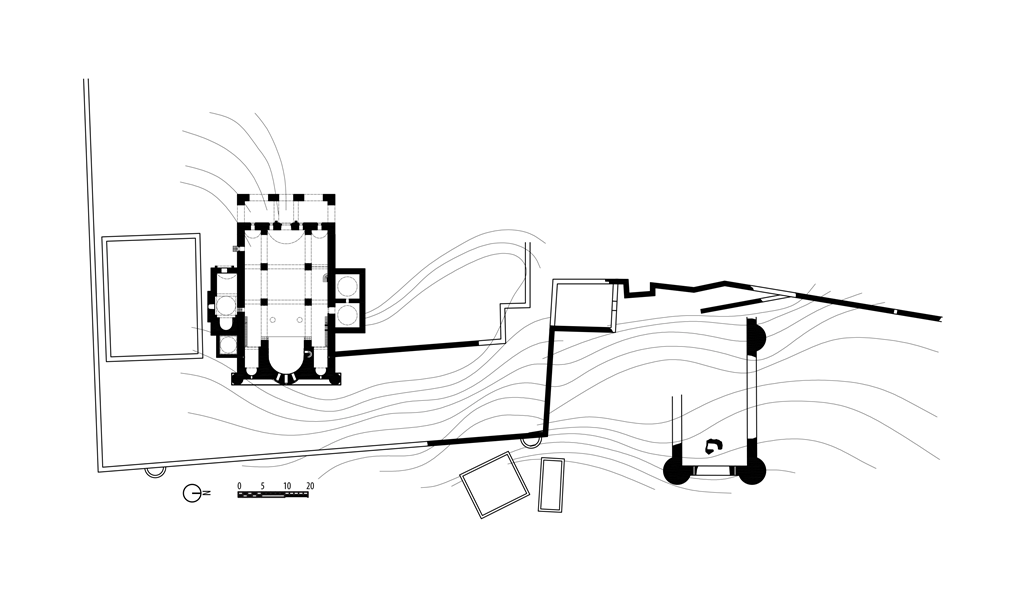

Plan d’après (Gergian-Nordiguian, Les Arméniens de Cilicie, 2012: Restitution du plan de la Cathédrale à partir d'un plan de R.Edwards,DOP, 1982, fig 24.)

• The cathedral church of Holy Wisdom (A), a palatine church founded in 1226, which became a patriarchal church in the 16th century and then was transformed and enlarged in 1797-1810: a tri-absidial basilica with a low saddleback roof over the central nave and two lower sloped roofs covering the narrower side aisles. Both side isles ended in two-tiered apses, one on either side of the central, semi-projecting apse. Four free-standing piers and four engaged piers, two of which were included in the triumphal arch, helped support the building, which was extended to the west by a porch with five arches; two of these were on the sides, and were surmounted by a balcony opening onto the interior. At some time before the 1850s, this balcony was replaced by an inside wooden balcony and the early openings made into windows. The church was lit by a series of windows and oculi placed high in the walls. In the interior, the walls and engaged piers were largely covered in earthenware tiles from Gudina [Kütahya]; near the first north pier stood the throne of the catholicos, facing the choir, and at the west end of the north nave, the tomb of Catholicos Cyriacus I, who built the church. A crypt or a cellar was entered through the choir. Rounded, projecting buttresses marked the north and south corners of the east wall. The cathedral church of Holy Wisdom, including the porch, measured nearly 40m in length and 20.4 m in width; with the buttresses, the east wall came to 22.4 meters.

Abside centrale de l'église Sainte-Sophie après la destruction de l'autel (Archives départementales de l’Eure, 36 Fi 788, fonds Gabriel Bretocq 1918-1922).

• The chapel of Saint Gregory the Illuminator (B), a domed building without drum measuring 5 × 5.4 m on the inside, adjoining the north wall of Holy Wisdom and communicating with it.

• Extending the previous chapel to the west and communicating with it, the chapel of the Holy Spirit (C), higher and measuring 5.4 × 5.5 m on the inside; domed as well, it housed the church treasure. The two chapels formed a bloc of 13.5 × 6.4 m along the north façade of the cathedral.

• Built against the south façade of the cathedral and communicating with it, the chapel of Holy Edchmiadzin (D), a single-nave vessel of around 14 × 6 m, surmounted by a facetted dome.

• At the corner of the east wall of the above chapel and the cathedral, stood a bell tower(E)with a footprint of 4.6 × 4.1 m, but which did not rise as high as that of Holy Wisdom.

• A convent yard wall that served as a retaining wall to the east and rose irregularly at an oblique angle westward up the rocky slope, tapering to a point at the top of the convent grounds. Dwellings were built against the south and north sides, above the earlier gates. A third, higher gate was opened in the north wall, giving access to the barn and stables.

• Outbuildings – kitchen, ovens, cellars, refectory, baths – and the seminary building.

• Various dwellings built parallel to the east courtyard wall or as free-standing pavilions.

• The patriarch’s residence, a vast cross-shaped construction with wood paneling; its great hall was decorated with wall paintings. Like the rest of the convent buildings, it was constructed between 1797 and 1810.

Plan générale restitution d’après (Gergian-Nordiguian, Les Arméniens de Cilicie, 2012: Restitution du plan de la Cathédrale à partir d'un plan de R.Edwards,DOP, 1982, fig 24.)

Among the dependencies of the Sis patriarchate was the farm of T‘il or T‘lan, which covered some 2,000 “arpents” – roughly acres – and had a mill. The convent also had a mill at Sis as well as houses, shops and gardens at Sis and Marash. The treasure was composed of several reliquaries, gold- and copperware, liturgical vestments – over 820 pieces – and a valuable library of 145 manuscripts.

The buildings of the catholicosate were confiscated after the retrocession of Cilicia to Turkey and were ravaged and methodically destroyed. The Old Convent has entirely disappeared. And of the New Convent only a few remains can be seen. Demolition of the church of Holy Wisdom had begun as early as 1915-1918. By 1943, all that remained of the cathedral was the absidal block; to the north, the chapels of Saint Gregory and the Holy Spirit had been razed, and to the south, Holy Edchmiadzin had already been mutilated. At the back, only the lower half of the bell tower still stood. By the 1980s, all that could be seen of these ruins were the two bottom courses of the east wall of Holy Wisdom, the cellar of the choir and a few sections of the wall of Holy Edchmiadzin, which were still visible in 2009. A reservoir had been dug on the site of the nave and the north chapels of the cathedral, before being planted in trees. Only a very few pieces of the Sis treasure were salvaged, among which was the right hand of Gregory the Illuminator. All the manuscripts have disappeared or been destroyed, with two exceptions: the famous illuminated Gospel of Partzerpert [***], dated 1248, and what is known as the big ceremonial “of Sis”, dating most certainly from 1311, in which several catholicos since the 16th century have written in their own hand the mention of their accession to the throne.

In April 2015, Aram I, Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia, applied to the Constitutional Court of Ankara for restitution of the patriarchal convent of Sis, its adjoining buildings and its dependencies. Pending a decision, the constitutional court transmitted the Catholicos’ petition to the Turkish Ministry of Justice. The adverse opinion delivered by the Ministry in May 2016 was contested by the catholicosate within the required period of time.

Vue sud de la chapelle Saint-Édchmiadzin, 1943 (Kéléchian, 1949, 749).

Berbérian, 1871, 98-101, 166-167. Bezdiguian, 1927, passim. Savalaniants, 1931, i, 550 ; ii, 902-906. Ormanian, 1959-1961, ***, 1959. Pivazian, 1960, 12-33, 197-204, 265-273. Album, 1965, passim. Akinian, 1968, 251-272. Éghiayan, 1975, ***. Aznavorian, 1978, 16-17, 29-51. Edwards, 1982, 168-170, fig. 24-29. Edwards, 1983, 134-141, fig. 47-66. Taniélian, 1984, ix, 90, 96. Gulésserian, 1990, passim. Djemdjémian, 1996, 226. Correspondance, 1999, passim. Mutafian, Van Lauwe, 2001, 76-77. Dédeyan, 2003, ii, 1264-1268. Kévonian, 2004, 27-136. Tachdjian, 2004, ***. Kévorkian, 2006, 832-839. Mutafian, 2012, i, 224.