From Hatamaguerd [Başkale], the road to the monastery of Saint Bartholomew leads back up the valley of Medzn Zav, or Great Zab [Zap], in the Armenian canton of Medzn Aghpag, or Great Aghpag. The monastery is located at 38° 08’ N and 44° 12’ E, on the right bank of the river bearing, at this spot, the name of Ashguerd, on a vast mound that dominates the village below: Alpayrag [Zapbaşı] or simply Vank‘: “Monastery”.

Several traditions associate the foundation of this monastery with the Apostle Saint Bartholomew, with King Sanadroug (1st half of the 2nd century) or with King Tiridate IV and Saint Gregory the Illuminator (1st half of the 4th century). Tradition held that this spot housed the remains of Saint Bartholomew, who, after stopping at the convent of the Spirits (n° 31), was martyred here. This claim should be confronted with another tradition, which places the tomb of the Apostle Thaddeus (also known as Saint Jude) in the north of Vasbouragan, on the site of the monastery of Saint Thaddeus, today in northern Iran. That is why the mountainous territory in which these two sanctuaries lie has been called Arak‘elots Erguir, “Country of the Apostles”. The monastery is mentioned in the first half of the 10th century by the name of desert of Ashe (Asho Anabad) or convent of Ashad (Ashada Vank‘), and then in 1316 under the name of Saint Bartholomew. Its superior, James (Hagop), attended the council that met at that time in Adana, in Cilicia. In the 14th and 15th centuries, Saint Bartholomew was one of the major seats of the Armenian Church: its superiors, who carried the title of archbishop, were primates of the diocese of Aghpag. The monastery also had its own scriptorium. At the time of the prior and great Church doctor Cyriacus (Guiragos, † 1457), it housed some thirty monks. The Aghpag school was still flourishing at the end of the 15th century, when, under the abbot, Archbishop John (Hovhannès), the philosopher-monk Lazarus (Ghazar) was a well-known authority.

Façade sud, funérailles d'un Arménien assassiné par des Kurdes (N. et H. Buxton, 1914, p.32).

In the 16th century, like many other convents, the monastery went into a slow decline. It was not until the arrival as patriarch of Edchmiadzin of the energetic Philip I of Aghpag (P‘ilibbos Aghpaguétsi, 1633-1655), who came from the region, that the abbot, Cyriacus II of Avants and also superior of the Holy Cross of Varak (n° 1), completed in 1651 the restoration of the monastery buildings. Between 1659 and 1667, the monastery’s prior, Isaiah (Essayi), continued working at the enhancement of his seat, whose jurisdiction extended as far as Salmasd to the east and which, as it finally encompassed Urmia, in the 18th-19th centuries, eventually included the entire western shore of Lake Urmia in northern Iran. Toppled by the 1715 earthquake, the drum of the church was rebuilt in 1755 by the abbot, John of Mogs (Hovhannès Mogatsi), from the Lim desert (n° 3) congregation. Appointment of the abbot of Saint Bartholomew became a subject of discord and negotiations between the catholcios of Edchmiadzin, the Kurdish lord of Hakkiari and the faithful, over the period from 1766 to1817. In 1843, following the establishment of the Russo-Persian border along the Arax in 1828, the abbotships of the two apostolic monasteries of Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thaddeus were temporarily fused. Damaged again by an earthquake in 1860, the drum of the church was restored by Doctor Eghiazar in 1877-1878, while a new earthquake in 1897 made it necessary to consolidate the church walls. At the beginning of the 20th century, the monastery’s jurisdiction took in 26 localities and 23 churches, among which the priory of Saint Edchmiadzin of Sorader (n° 33). From time immemorial, Saint Bartholomew has been the site of a major pilgrimage: the custom, mentioned as early as the 9th century, was to offer white cows on this occasion.

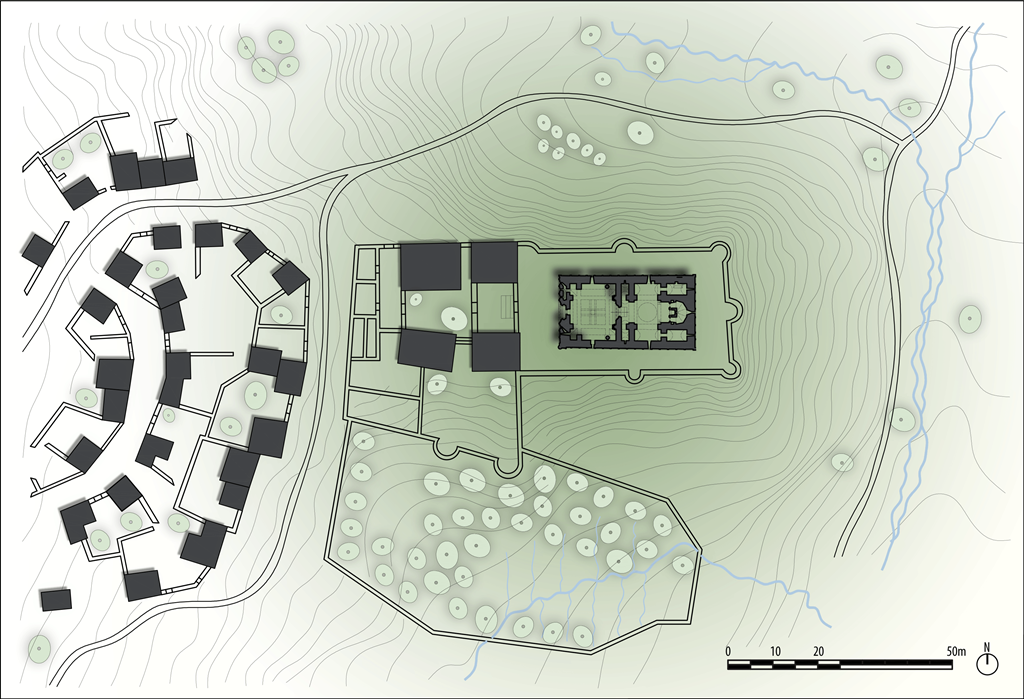

The monastery of Saint Bartholomew includes:

General plan (modified after Bachmann)

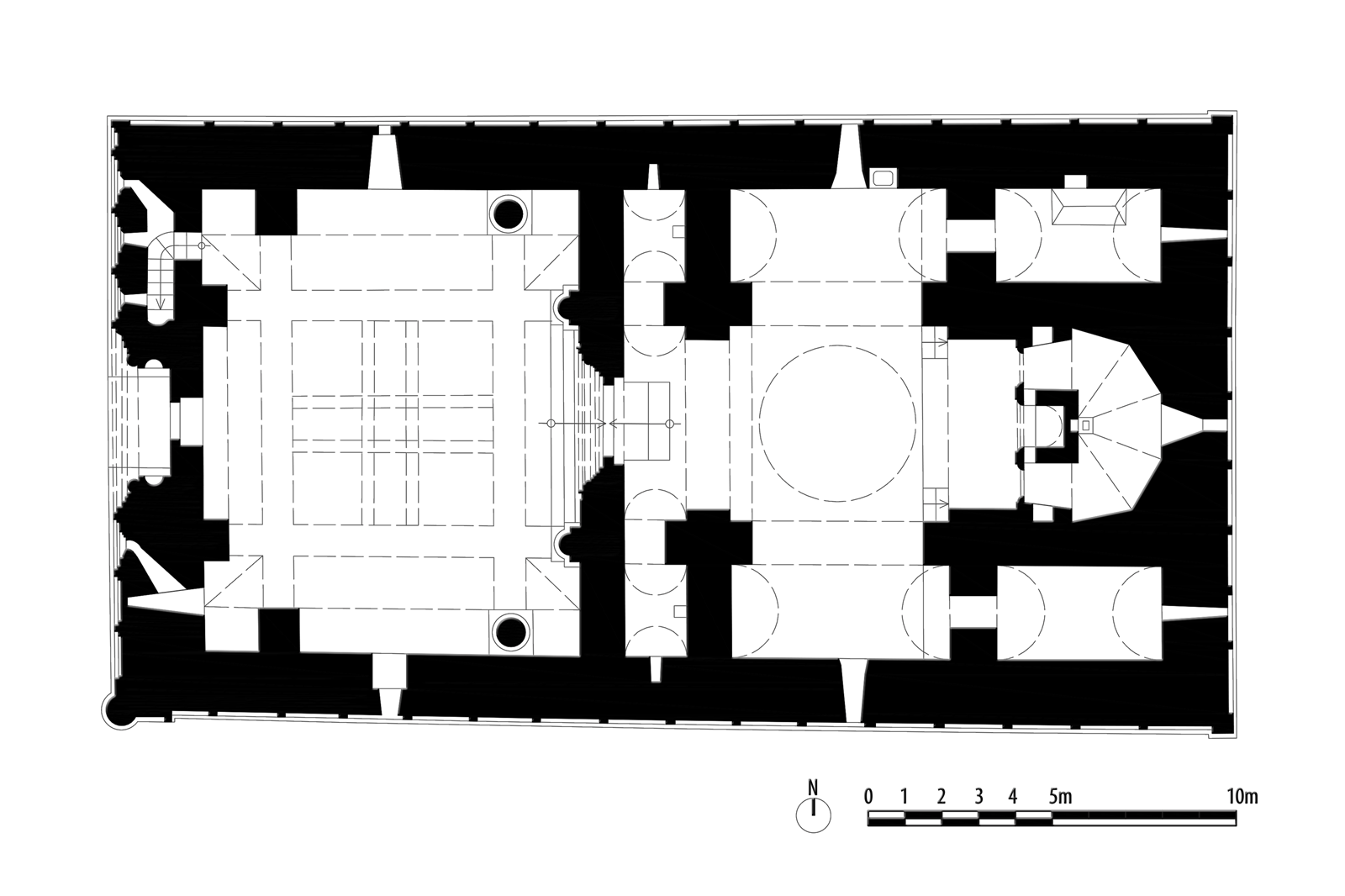

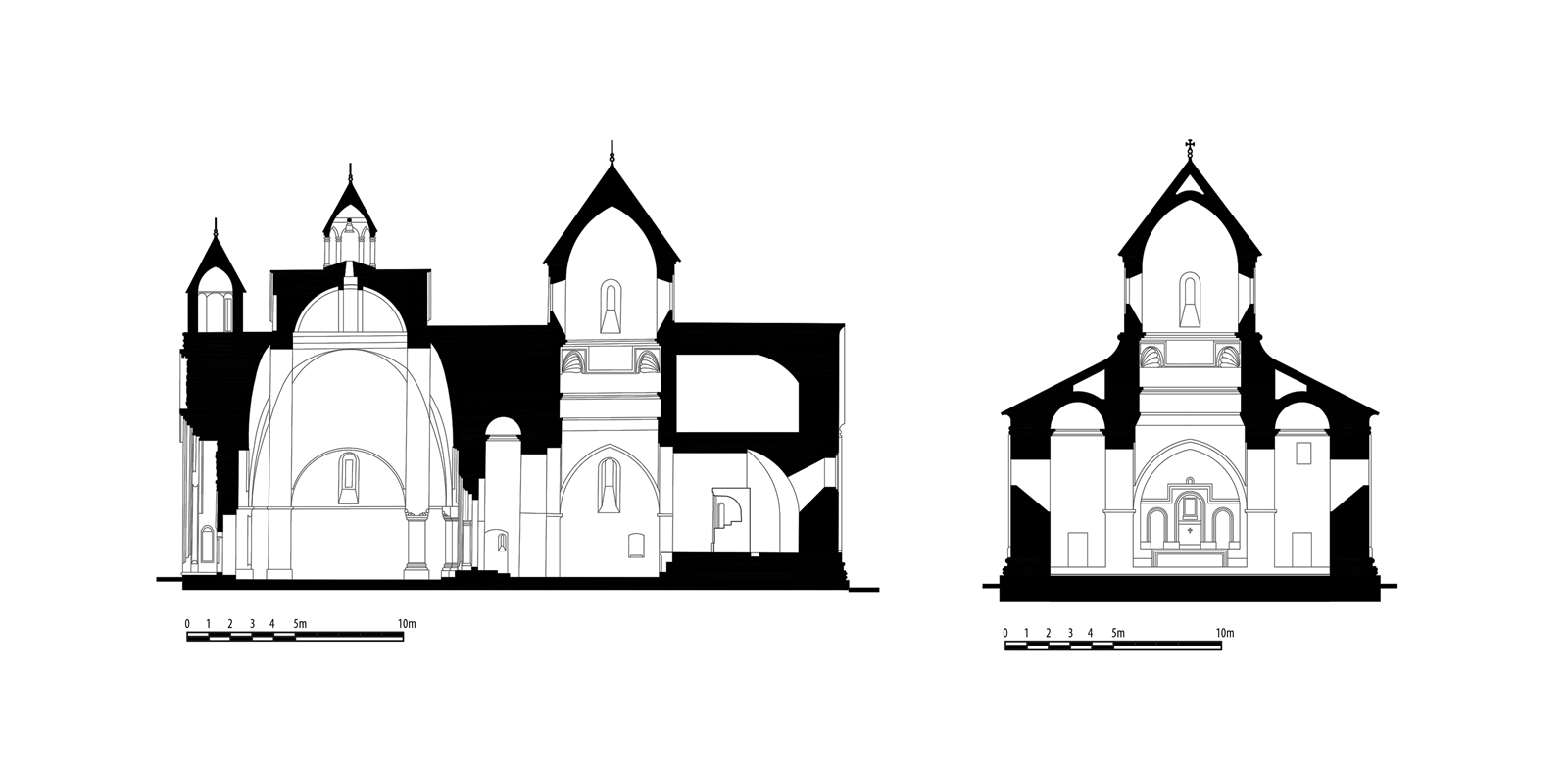

• The church: a cross-in-square whose typology links it to structures of the 13th and 14th centuries, the church very probably stands on the site of a paleo-Christian basilica built on steps, of which remain, aside from the base, the eastern part, in which the east arm and the central apse are disposed – flanked by two side chambers – and higher up, an enclosed, vaulted space that forms a second level. The north chamber holds the funeral chapel dedicated to Saint Bartholomew and the right-hand chamber to the south, the altar of the chiliarch (hazarabed), a dignitary of the entourage of King Sanadroug cured of leprosy by the water from a nearby spring. The church is surmounted by a twelve-sided drum with pyramid, renovated in the mid 17th century with alternating horizontal bands of black and colored stone, rebuilt again in 1755 and once again restored in 1877-1878.

• Extending directly west from the church, a narthex with eight engaged columns supporting four crossing arches which, on a second level, enable four more crossing arches to frame an opening in the center surmounted by a columned lantern. Access is gained through a large door with a carved double tympanum, the lower tympanum representing fighting horsemen, perhaps a re-utilized ancient stone, and the upper representing a trinitarian theophany. A small bell-turret once sat atop the façade. The church and narthex dating from the same period form a bloc 31 × 16.5 meters with façades decorated with a succession of molded frames. The saddle-back roof of the narthex with its side aisles rises above the slopes of the church roof.

Plan (modified after Bachmann)

Sections (modified after Bachmann)

• Common buildings grouped to the west of the churchyard and the narthex: stables, sheepfolds, hay barn in the first forecourt; dwellings, storage, bursar’s office and pantry in the second.

• A hostelry or house outside the walls, situated to the north, which also once housed a school.

• An irregular precinct wall with towers, measuring some 350 m, against the north side of which a mill was built.

The monastery owned plow lands, pastures and woods.

The Saint Bartholomew monastery was confiscated after the Great War and included in a military camp. Nevertheless, its buildings went unprotected. The 1966 earthquake resulted in the collapse of the church’s drum, the narthex roof and the upper tympanum. The army withdrew from the site in 2012, leaving a dramatically mutilated monument, all of the covering slabs of which had been torn off up to the middle of certain facades. The commons and yard walls have all disappeared.

Vue générale nord-est, 1980 (Coll. Gazarian).

Oskian, 1940-1947, III [1947], 785-805. Darbinian-Mélikian, 1971, 110. Thierry, 1989, 471-477. Devgants, 1991, 297-304. Mirakhorian, 2013, 221-227.