The Holy Precursor monastery of Moush [Muş], built hard against Mount K‘ark‘é [Bazmasar, Ciligöl] to the northwest of this town, at 38° 57’ N and 41° 11’E, is not only the foremost monastery of the Taronid – the Armenian canton of Darôn and the principality of which it was the center – but one of the largest and most important monasteries in western Armenia, and no doubt the most famous of all. Its repute stems from the fact that the monastery perpetuates the tradition of the re-foundation of the Armenian Church by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, whose preaching, at the beginning of the 4th century, resulted in the conversion of King Tiridate IV (Dërtad) and his kingdom to Christianity. Saint Gregory’s predication is particularly rooted in this region where the first church founded by the Illuminator is thought to have been built precisely at Ashdishad, formerly one of the major sanctuaries of pre-Christian Armenia (see n° 57). Bringing with him relics of the Holy Precursor John the Baptist and of Saint Athenogenes as gifts, Saint Gregory bestowed them nearby, on either side of the valley of the eastern Euphrates or Aradzani [Murat Çay], on the north side on what would become the Holy Precursor monastery and on the south side on the monastery of Saint John (n° 56).

In this region as well as in several others, the House of Saint Gregory together with the Church would be granted important prerogatives, while Ashidishad would remain the seat of the first heads of the Armenian Church, all of whom were from the Illuminator’s family. In the 5th century, the Darôn was a possession of the Mamigonians, the dynasty that provided the Armenian kingdom with its military leaders; this family had been allied since the 4th century with that of Saint Gregory. The catholicos, Saint Sahag the Great (387-438), scion of both families and a direct descendant of the Illuminator, together with Saint Mesrob Mashdots, also born in Darôn, created the Armenian alphabet circa 405, under the reign of Vramshabuh. Later, after King Artaxias IV (Ardashès) was deposed in 428, Saint Sahag’s grandson, Vartan Marmigonian, would lead a general uprising against the Persians and would die for his faith at the battle of Avarayr, in 451. Owing to these circumstances, the Darôn gradually acquired a singular place in the sacred geography of Armenia, illustrated not only by Saint Gregory’s predication and works but also by the successive struggles for the Armenian language, writing and faith. Among other regions marked by the presence of the Illuminator, Mount Sebuh [Kara Dağ], in upper Armenia, is associated with his retreat and his death (see n° 44-47).

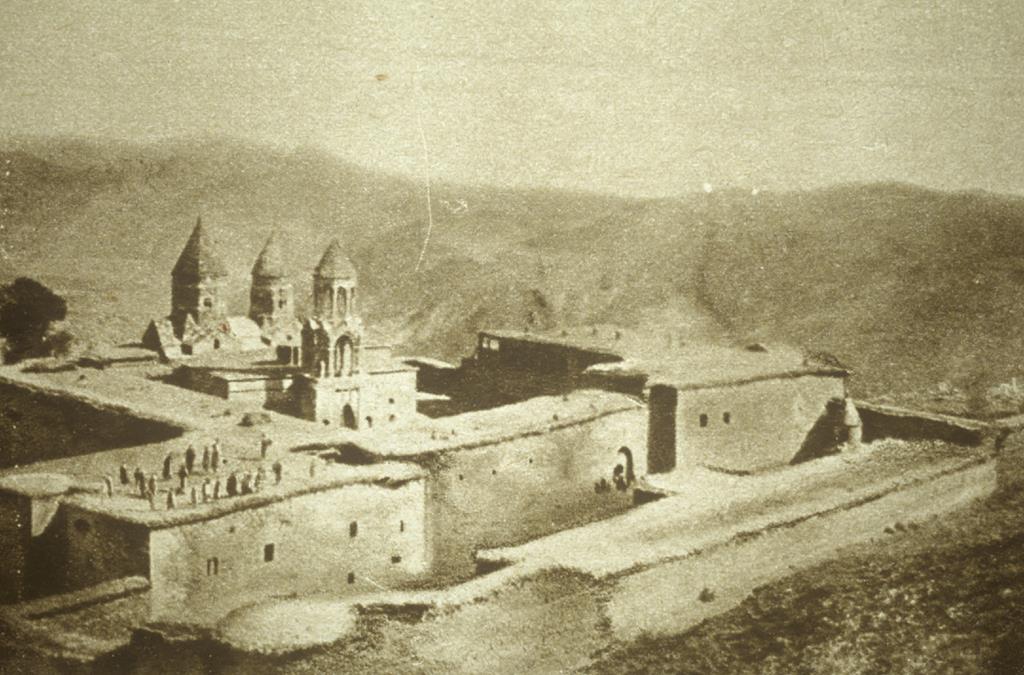

Vue générale nord-ouest, avant 1892 (Pisson, 1892, 23 [gravure, par Scott] ; Le Miroir, 5 mars 1916).

After the ruin of Ashdishad, three foundations in turn perpetuated its symbolism: the Saint John monastery (n° 56), which had received a share of the Illuminator’s gifts; the Holy Apostles monastery (n° 54), whose dedication to the Translators clearly refers to the inventors of the alphabet; and last but not least the Holy Precursor monastery (Surp Garabed). The latter, without a doubt built on an ancient site, was also at the time of the Illuminator the retreat of the anchorites Anthony and Chronides, two Greek companions of Saint Gregory. Yet, tradition holds that the first superior of the new sanctuary was the Syrian, Zenop, known as Klag, whose brother Lazarus is said to been head of the Holy Apostles monastery, hence its other name, Klagavank‘, or “Klag’s convent”. It also bears the name of the mountains where it stands, the Innaguian mountains, or mountains “Of the Nine Springs”, which border the valley of the eastern Euphrates north of Moush. The prestige of this “Gregorian” monastery grew over time to the point where, in the 19th century, on the feast of the Transfiguration, or Vartavar, it was the site of the largest pilgrimage in eastern Armenia, which drew the faithful from sometimes great distances. From Moush, the pilgrims’ route usually led through Karni [Ağaçlık], Hadj Manug [Güzeltepe], Avzaghpiur [Özdilek], Kheybian [ Yoncalıöz], Meghdi [Yaygın] and Sordar [Aşağıyongalı]; then from there along Mount Sergui [***], through the Neghp‘oghan [***] passage and up to the Havadamk‘ (Credo) ledge at an altitude of some 2100 m; from there, with the monastery now in view, the pilgrims arrived directly at the southern gate of the wall. Several other routes existed as well.

If the History of the Darôn, written around 970 by an author concealed behind the features of John (Hovhannnès) Mamigonian, a prior supposed to have lived in the 7th century, does not provide sufficiently reliable information on the early history of this establishment, it nevertheless suggests that this foundation, surely consisting of a simple martyrium at the start, was served until the second quarter of the 7th century by a Syriac-speaking clergy. The History combines the remains of Anthony and Chronides with those of seven hermits killed by Persians at the time of Prince Mushegh Mamigonian († 604) – to whom it ascribes a first restoration of the sanctuary – and of his relative Kayl Vahan († 606), both of whom are buried there. It is supposed that in the 8th century the Holy Precursor was already the seat of the see of Darôn, and no doubt had been since the destruction of Ashdishad by the Arabs. Gregory (Krikor) Bahlavuni, or Gregory Magistrus († 1059), a famous erudite prince, established his academy there in the 1040s, which was attended by none other than the abbot of the Holy Precursor, Sergius (Sarkis). Gregory also built a residence there, and a narthex in front of the church, a wood-framed building at the time. In 1058 the monastery was targeted by Seljukid troops, which burned it. Victorious over the latter, T‘ornig Mamigonian († 1072), Gregory Magistrus’ son-in-law and master of the region, would later also be buried there.

Église Saint-Étienne : absidiole nord, 2014 (Coll. M. Gazarian).

The martyrium or Holy Precursor church, reconstructed as a nave with dome, is certainly the oldest part of the monastery, there where the relics of the Precursor and Saint Athenogenes were installed, their tombs being built at a later date. A great age is also attributed to the Holy Mother of God church, situated further to the north, which an unverifiable tradition attributes to the patrician, Vart, a 7th-century Ardzrunid prince; Vart is supposed to have built the church in memory of his wife, who was killed for having broken the taboo – attributed to the Syrian clergy – on women approaching John the Baptist’s tomb. Judging by the ground plan, it was sometime between the 10th and 12th centuries that the Saint Stephen Protomartyr church, with its drum and dome, was built between the other two churches. At an undetermined date, another martyrium was erected to the south of this complex in honor of Anthony, Chronides and the seven hermits. A Resurrection chapel (Surp Harut‘iun), later included within the walls of the monastery, also imprisoned beneath its floor the devils defeated by the Illuminator. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Holy Precursor monastery, whose abbots held the rank of archbishop, was a scriptorium and a recognized place of learning, where the scholar and poet John of Erzenga [Erzincan] (Hovhannès Erzengatsi, † 1293, see n° 45) had stayed: “The gates of Hell were shattered / In this place of the Nine Springs they were cast down / Whence the troops of devils were driven off / Where the angels arrayed themselves at our side”. After the fall of Martyropolis, or Nëpërguerd [Mîyafarkîn, Silvan] in 1408, the monastery was enriched by an important share of the relics conserved in this city, the rest of which went toward re-founding, in 1434, the monastery of the Holy Mother of God of the Sweeping View of Arghën [Ergani] (n° 67).

The influence of the Holy Precursor monastery at Moush reached beyond the Taronid as far as Garin [Erzurum] and Erzenga [Erzincan], so that many monasteries claiming a direct or indirect connection with Saint John the Baptist, the Illuminator or their symbolic association, formed a network around the Moush monastery. Such was the case, for example, of the monasteries of Saint David of Abrank‘ (n° 40), and of the Holy Mother of God Overlooking the River (n° 60), or that of the Holy Precursor of K‘ëghi [Kiğı], whose prior, Melchisedech (Melk‘isset, 1442, 1450), had, it seems, his imposing cross-stone (1460) at the Holy Precursor of Moush – to whose congregation he had no doubt belonged. It was during these years that Abbot John (Hovhannès), martyred in 1463 at Pagesh [Bitlis], undertook the restoration of the church of the Precursor and that of Saint Stephen. His work was continued in 1481 by Abbot Baptist (Mgrditch), who renovated the domes of the Precursor, Saint Stephen and the Holy Resurrection, then, under his successor, by Gregory of Darôn (Krikor Darôntsi, † c. 1523-1524), the builder-monk who distinguished himself at the beginning of the 16th century in several other places (see n° 46 and 56). Gregory renovated the pavements of the churches and their narthex, half of the monks’ cells and the bursar’s office; above all he built or rebuilt a wall around the monastery. Perhaps the construction of a new church against the south wall of the Holy Precursor and dedicated to Saint George is also the work of one of these prelates. The period was further marked by continual scriptural activity, represented in particular by the illuminator and copyist, Mardiros, joined around 1525 by the poet and copyist, Garabed of Pagesh (Garabed Paghichetsi), before the latter settled at the nearby monastery of the Holy Apostles (see n° 54).

In the present case, the 16th century does not seem to have been marked by decline, in spite of increased pressure on the monasteries. With the help of Khodja Budakh of Arjesh [Erciş], Abbot Melchisedech II († before 1563) augmented the area of the main narthex, which already served as a church and which he then rested on eight free-standing columns instead of four. The fame of the monastery already suggested it as a rival to Edchmiadzin, where it was intended to install Sahag IV (1624-1628), coadjutor of the sitting catholicos. Beginning in 1654, it fell to Abbot Arisdaguès II to renovate several parts of the monastery: drums and roofs of the Holy Precursor and Saint Stephen churches, covered in lead at the time; monastery wall; fountain; main gate with its iron-reinforced doors; and the Seven Hermits church. At the beginning of the 18th century, the arrival of two Church Doctors from the Amirdol school (n° 59) – Gregory the Enchained (Krikor Chëght‘ayaguir), elected abbot in 1704 and later patriarch of Jerusalem (Gregory VII, 1715-1749), and John the Lesser (Hovhannès Golod), who would in turn become patriarch of Constantinople (John IX, 1715-1741) – shortly preceded the 1709 earthquake, whose damages they repaired bit by bit, in addition to building a bell tower in front of the narthex. The reputation of Moush’s Holy Precursor allowed them to enlist Yaghub amira Hovhannessian († 1752), one of the major Armenian merchants and money-changers in Constantinople, in the financing of this undertaking, and it was he who completed the restoration of the monastery complex. Over this century, two of the monastery’s superiors, Abraham of Kegh (an Armenian canton to the east of Nëpërguerd [Mîyafarkîn, Silvan], Apraham Keghetsi, 1716-1730) and Menas d’Agn [Eğin] (Minas Agntsi, 1730-1749), would also occupy the see of Edchmiadzin as Catholicos of All Armenians under the names of Abraham II (1730-1734) and Menas I (1751-1753).

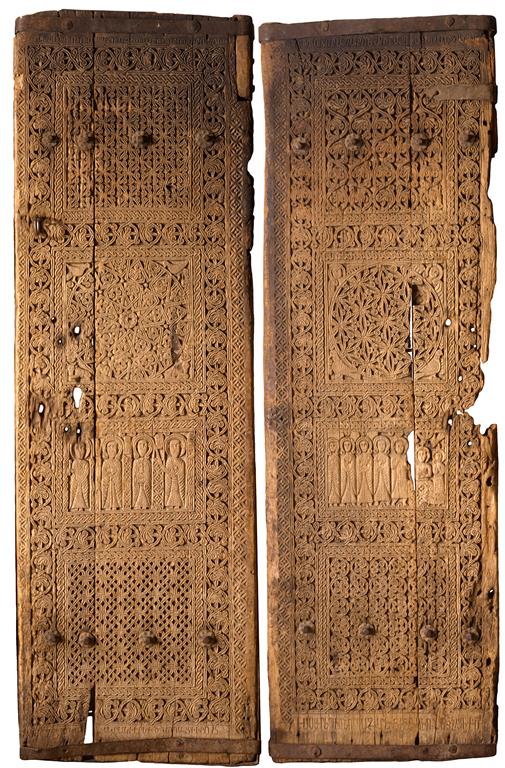

Porte sculptée ayant probablement appartenu à l'église du Saint-Précurseur, datée de 1512 (Mutafian, 2012, II, fig. 212, coll. particulière).

Yet the 18th century saw a second earthquake, in 1784, which caused in particular the collapse of Saint Stephen’s dome, which Abbot Asdwadzadur reconstructed in the space of three years together with the refectory, the dwellings, the south wall and several towers. Above all he once again increased the area of the main narthex, extending it to the west with eight more columns, and integrating the foot of the earlier bell tower. The bloc formed by the sanctuaries and the narthex – which itself had become the biggest church – was then given a magnificent new bell tower. The Holy Precursor saw some dark hours over the following century. In 1807, Yussuf Pacha had the superior, Hagop (James), assassinated on the road to Moush. Then on 27 June 1827, armed Kurdish gangs attacked and plundered the monastery, making off with a large part of its treasure and community goods, destroying or carrying away most of the art objects and paintings, among which a large, particularly admired Last Judgment, and above all causing the loss of a great many ancient manuscripts, some of which were thrown in the water and others ground up at the mill. After the buildings had stood empty for six months, the prior, Bedros (Peter) of Gouraw [Şenobalı], recovered possession of the monastery and attempted to repair the damage, beginning by restoring the tomb of John the Baptist. The Holy Precursor then became what it had already been at the turn of the 19th century, the seat of a single diocese composed of Moush and Garin [Erzurum], which it would remain until the 1840s.

Successive priors expend considerable effort in restoring the monastery, despite an earthquake in 1866 and more pillaging by the Kurds in 1877; in 1878 its community numbered 180 religious and laypersons. Noteworthy among the initiatives were the realization of decorative elements in the interior and of artworks, reconstitution of a library, installation of a printing press, construction of a school, as well as different renovations to which the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople would soon devote a global program. Pride of place should be given to: Father Mgrditch Khrimian (1862-1869), “Little Father” (Hayrig) of the people and former superior of the Varak Holy Cross monastery (n° 1), later patriarch of Constantinople (1869-1873) and then catholicos of Edchmiadzin (1892-1907), who published there the Ardzwig Darôno, “Eagle of Darôn”; to Archbishop Mampré Mamigonian (1874-1882), who recovered a portion of the spoils from the Kurdish beys; and finally to Father Karekin Srwantzdiants, first vicar and then abbot of Khrimian (1888), a competent administrator and famous author of Brother Theodore, Traveler in Armenia (Constantinople, 1879, 1884), a long account of his travels from monastery to monastery and library to library, and compilation of inscriptions and colophons contained in manuscripts, most of which have disappeared. The last superior of the Holy Precursor of Moush was Father Vartan Hagopian, who was made bishop of Moush in 1915 and martyred the same year. At the time of the genocide, when the monastery was already being used to garrison troops, part of the population of the foothill villages took refuge not far away, on the slopes of Mount Sergui and in the surrounding forests in an attempt to escape massacre. In 1916, when the Russian troops reached Moush, the Turkish army and its auxiliaries had already plundered and destroyed a large portion of this holy place.

Vue du clocher et du bloc des églises après leur destruction par l'armée turque, 1916.

For a long time the jurisdiction of the Holy Precursor of Moush encompassed the entire surrounding region – extending sometimes as far as Garin/Erzeroum –before Moush was made an archbishopric. In 1910 the archbishopric included 332 localities and 230 churches. The Holy Precursor monastery was abundantly endowed with plow lands and pasturage. The priories of Saint Daniel of Gop‘ [Bulanık] (n° 58) and Madravank‘, or Madnavank‘, also answered to the Holy Precursor monastery; the latter was located north of Moush near the village of Tsëkhdu [***], and itself had authority over Saint Sahag’s funeral chapel (n° 57), which stands on the site of ancient Ashdishad, at Derig [Yücetepe]. Before the Great War, a collection of 12 old manuscripts dating from 1368 to 1727 had been reconstituted in the Holy Precursor library.

The Holy Precursor monastery of Moush, or Klagavank‘, included:

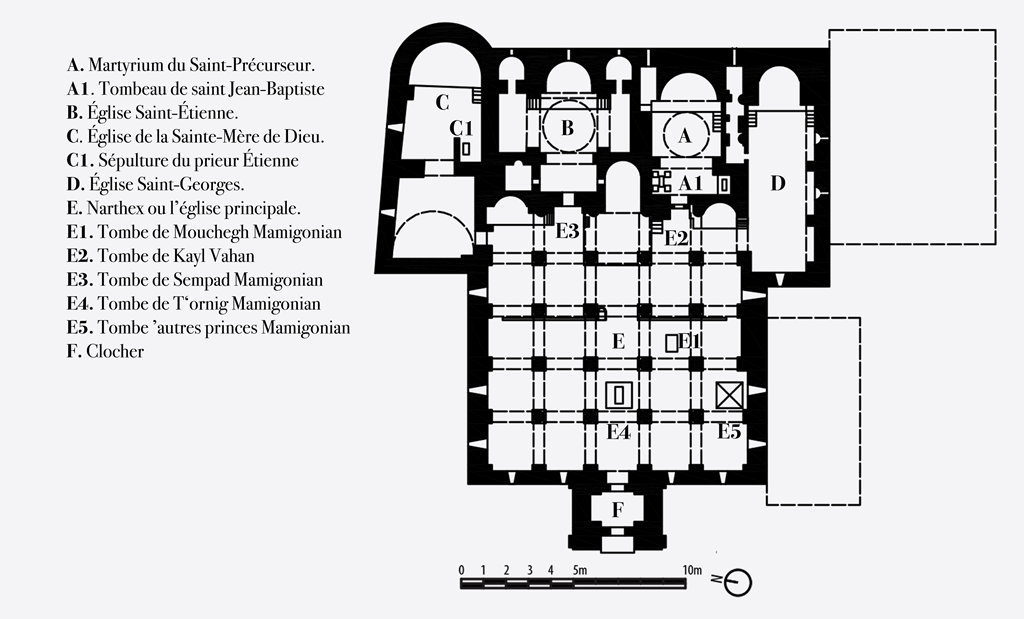

Églises, narthex et clocher : plan.

• The Holy Precursor martyrium or church (A), a mononave with drum some 10 m long on the inside, built after 1058 over an earlier sanctuary restored at the turn of the 7th century. The apse was originally flanked by two narrow absidioles. Restored in the 1460s and in 1481, and again in 1576, 1654 and 1709, the Holy Precursor church had been given an octagonal drum decorated with arches and a pyramid, which were renovated once more in 1901. The northwest corner of the western part of the nave housed the reliquary and tomb of Saint John the Baptist (A1), over which, in the 1830s, a two-tier baldachin had been built, supported by columns ringed with white marble; the tomb of Saint Athenogenes occupied the southwest corner. The façade of the choir platform was decorated with a series of cross-stones dated 1718. The altar was fitted with tall painted and gilded wood panels, made by the brothers Sarkis and Nigoghos, from Van, in 1839. A carved door dated 1512 (or 1312?), saved from destruction and now in a private collection, no doubt came from the Holy Precursor church.

• The church of Saint Stephen (B), a cross in square with drum measuring some 10 × 10 m on the inside, with large lateral niches under arches opening on the east into the absidioles, and side chambers occupying the two western corners, built between the 10th and 12th centuries north of the above church and precisely aligned with it. Like the Holy Precursor church, it was restored in the 1460s and in 1481, as well as in 1654. It was accessed through a door inlaid with amber and ebony and dated 1526. The octagonal drum and its coif were restored in 1784-1787 on the model of those of the Holy Precursor and were renovated in 1901-1902.The same woodcarvers and woodworkers from Van had also fitted the altar with impressive wood panels in 1842.

• The Holy Mother of God (C), a mononave with a barrel vault and projecting apse, some 11 m in length and traditionally dated to the 7th century. It contained the tomb of Prior Stephen (Sdep‘anos) (C1), son of the patrician, Vart, supposed to have built the church, as well as two cross-stones from the 11th and 13th centuries raised in memory of two philosopher-monks. Much later a narthex was added to this church, with which it formed a bloc of some 18.5 m from east to west. Following the 1866 earthquake, the narthex could be given only summary repairs. On pilgrimage days, the Mother of God church was reserved for Assyro-Chaldean worshippers

• Saint George (D), a single-nave church some 18 m long with a barrel vault, built against the south wall of the Holy Precursor probably in the 17th century. On the north side, it communicated with an oratory built into the south wall of this church, one of the absidioles of which had also been annexed for this purpose. Restored in 1844 but with cracks produced by the 1866 earthquake, the Saint George church could not be consolidated before the Great War. It was used as a library.

• The narthex, or main church (E). The first narthex, built or restored around the middle of the 11th century in front of the martyrium of the Precursor John the Baptist, was replaced by a narthex with four free-standing columns shared by the churches of the Holy Precursor and Saint Stephen, augmented in 1560 by four more columns and then, between 1784 and 1789, by eight more free-standing columns. With sixteen monolithic columns and sixteen engaged pillars surmounted by arches, delimiting five naves and five bays, this narthex became the main monastery church in which all of the others found themselves encapsulated. Sometime before the 16th century, it was given a central altar dedicated to the Holy Cross, which stood on the site of the original southwest chamber of the church of Saint Stephen, then two other altars situated at the ends of the first and fifth naves. The central altar, whose platform was adorned with early eighteenth-century cross-stones, was covered with a baldachin embellished with paintings and gilding done in the 1830s by the painter Mardiros of Van. This gradually enlarged narthex-church had encompassed several venerated and reputedly ancient monuments: the tomb of Mushegh Mamigonian (E1), those of Kayl Vahan (E2) (at the entrance of the Precursor’s martyrium) and his son Sempad Mamigonian (E3) (at the door of Saint Stephen’s), three 7th-century figures; those of T‘ornig Mamigonian (E4) (1072) and other princes (E5) from the same family; and some monks’ tombs. After the sack of the church, two new icons were placed near the central altar, opposite which had been placed a new abbatial throne, made in 1839. In the 1860s, Father Srwantzdiants had the columns and walls painted and decorated in green, red and blue.

• A three-story bell tower (F) with numerous carved ornaments and a rotunda, built in 1787, renovated in 1799 and again in 1902. This bell tower replaced an earlier one built at the beginning of the 18th century. The famous bells of the Holy Precursor of Moush won it the Turkish name of Tchangli [Çengilli-Çanlı kilise], the monastery “of the Rings”.

• In front of the bell tower, a church square delimited by a metal fence.

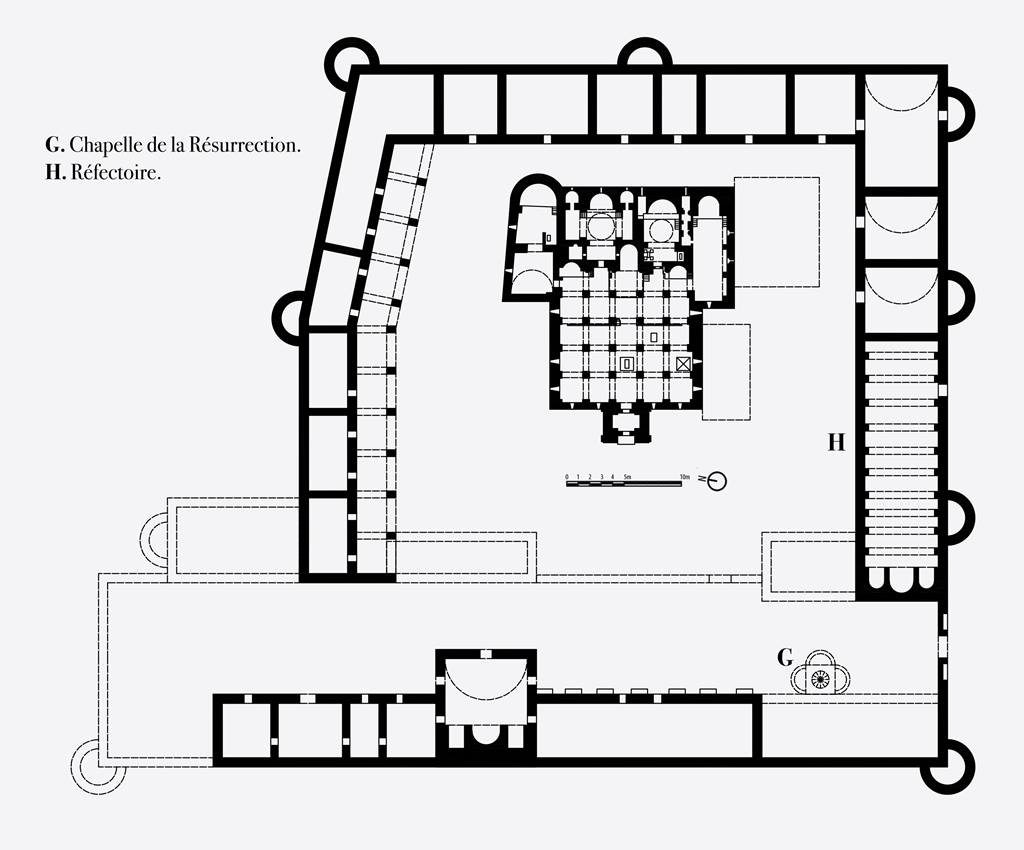

• A first yard wall with towers, built at the start of the 16th century and reworked, enclosing the main courtyard, or khachpag, surrounded by two tiers of outbuildings: prelacy, rebuilt in 1889; bursar’s office; dwellings; bread oven; refectory (H); mill; granary; storeroom; wood house; baths; schools (1850 and 1876); lodgings for pilgrims built along the north wall in 1825. Behind the chevets of the churches were the superiors’ tombs, among which Bishop Melchisedech’s (1460) cross-stone could be seen.

• The Resurrection chapel (G), to the southwest, a construction with a round drum and cone, built over a crypt, mentioned in the 15th century on the occasion of a first restoration and provided, around 1880, with a small wooden narthex. This chapel was included in a long courtyard that also contained a fountain, into which opened the big south door of the monastery that gave onto the courtyard of the churches.

• A second courtyard wall built in 1864-1865. This wall delimited, to the west, the courtyard of the Resurrection chapel and, to the north, a new and bigger courtyard where the barn, the stables and the grooms’ quarters were aligned. There under a twin arch, stood the healing fountain of the Illuminator, restored in 1654.

Plan du monastère(d’après Astuacaturean).

Outside the walls:

• Outside the south wall, the monks’ cemetery, where, among others, a 12th–13th-century cross-stone stood.

• Close to the south wall as well, the funeral chapel of Anthony and Chronides and the seven hermits, restored in 1654.

• The farm known as the Upper Dome (Verin Kmpet‘), set in the middle of monastery lands near the village of Gwars [***], northwest of Mount K‘ark‘é, composed of a sheepfold and stables.

• The Upper Farm (Verin P‘aguiah), situated a short distance below the wall, stands on the Arevelatzor ledge, surrounded by a high wall built in 1775-1780. The farm included a barn with a large pillared porch renovated in 1905, stables, an oil press, dwellings and a chapel – Saint Sergius – restored at the turn of the 19th century.

• The hermit-monks’ caves, carved into the rock at the foot of the Havadamk‘ ledge, on the south side, in the middle of the woods.

• The Lower Farm (Nerk‘in P‘aguiah), situated southeast of the monastery on the edge of a plain, between Meghdi and Sordar. It included a vast pillared sheepfold, renovated in 1902, a triple watermill, built upstream and fed by the waters descending from the monastery and from the village of Sahag Pazu [Bilek], and the Saint Paul chapel, restored at the beginning of the 1900s.

The ruins of the Holy Precursor monastery, already partially demolished by the Turkish army in 1915, were confiscated and left empty. Still visible in the 1970s, they were systematically used as a source of stone. Subsequently, as in many places, the authorities settled displaced populations there, who used the remainder of the ruins to build makeshift houses in the midst of the rubble. Today all that remains of this exceptional complex are a few sections of wall and pieces of the vaulted ceiling.

Mrmrian, 1906, 9-10. Loussararian, 1912, passim. A.To, 1912, 113-115. Kossian, 1925-1926, I, 116-128. Oskian, 1953, 134-244. Chahnazarian, 1956, 25-27. Oskian, 1962, 173. Mouradian & Mardirossian, 1967, 106-107, 218-219. Thierry, 1983, 388-398. Decgants, 1985, 55-62. Der Garabédian, 2003, 19-60. Greenwood, 2014, 377-392.