This famous monastery, more often known as Varakavank‘ or Varak monastery, is divided into a lower and an upper convent. The first is located some ten kilometers east of Van at 38° 26’ N and 43° 27’ E, at an altitude of 2100 m at the mouth of a small valley and at the foot of the southern slope of Mount Varak [Erek Dağ]. The second is an hour’s walk uphill. Today, the ruins of the lower convent hold the hamlet of Bakraçlı.

The historical roots of these sites go back to the next-to-the last episode of the Story of Hripsimé and the Holy Women – a group of Christian women led by Saint Hripsimé, whose martyrdom at the turn of the 4th century is central to the Kingdom of Armenia’s conversion to Christianity. After having visited Mount Sebuh [Bakraçlı] (see n° 45), stopping at the future monastery of the Holy Women (n° 29) and then at the Holy Lady monastery (n° 32) and the convent of the Spirits (n° 31), Hripsimé and her companions spent some time on Mount Varak but soon departed after having deposited a relic of the True Cross. The invention of this relic, which has since disappeared, is attributed to two hermits who lived on this mountain in the 7th century, T‘eotig, or T‘otig, and his disciple Hovel. The Holy Sign – or Holy Cross – of Varak gave its name to the church and to the monasteries founded to house it. To protect it from the Arab incursions, around the middle of the 9th century, the relic was temporarily concealed in the walls of the Holy Cross monastery in Aghpag (n° 33), in the hinterlands of the Ardzrunid princely domains. As the Armenians gained power in the 10th century, the monastery also gained in importance. King Kakig of Vasburagan (914-943) endowed the Holy Sign with a richly ornamented reliquary; the Catholicos elected in 946, Ananias I of Mogs (Anania Mogatsi, † 968) was none other than the abbot of Varak, previously a member of the community of the Holy Women monastery.

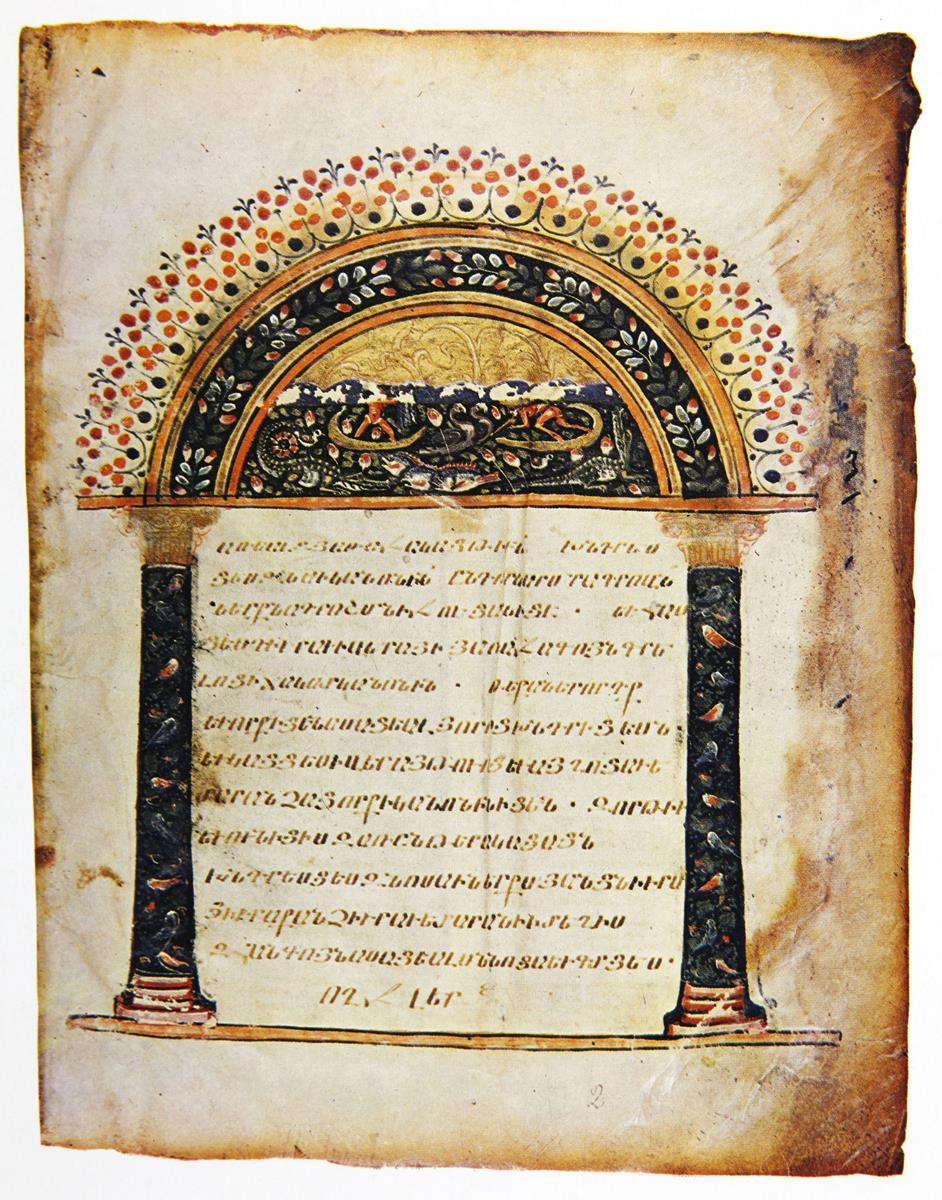

The monastery consists of two complexes, which grew over time, several of their elements being restored over the centuries. This is particularly the case of the lower convent, later to be known in Turkish as the “Seven Churches” [Yedi Kilise]. We do not actually know if the early church of the Holy Cross was part of the lower convent and if, redesigned, it subsequently became the later church of the Holy Mother of God located in this complex. In all events, tradition associates the name of King Senek‘erim-John (Sénék‘érim-Hovhannès, 990-1023, † 1025) with this church patterned on an older model. But a second church of the Mother of God, the main church of the upper convent, is also held to be very old. In all events, Queen Mlk‘é founded or restored one of the churches in 922 and at the same time donated a 9th-century evangelarium, or Gospel book, one of the oldest extant Armenian manuscripts. Queen Mlk‘é’s evangelarium has been held to ransom a number of times but has always been redeemed, the first time in 1208 by a group of monks, and later, probably at the start of the 16th century, by Lady Avakdiguin,. Each time, it was returned to the Varak treasury, and today it is safely housed in Venice.

Évangéliaire de la reine Mlk‘é, datant de 862. Lettre d'Eusèbe, scène nilotique. Venise, Bibl. Mekhitariste, ms. n° 1144, fol. 8 (Der Nersessian, 1977, 84).

According to one inscription, Queen Kushkush built the church of Saint Sophia in the lower convent in 981, and perhaps the adjoining church of Saint John as well. Both the lower and upper convents continued to grow according to a prediction that the synaxarion ascribes to the miraculous message delivered by twelve celestial rays designating the location of the same number of churches. Owing to the reputation of Varak, the convent’s superior Paul (Bôghos) was chosen in the second half of the 11th century by Prince Philaretès (P‘ilardos Varajnouni) to become Catholicos in his states, after the superior of the convent of the Spirits (n° 31) had declined the honor. Varak also gave its name to Nor Varakavank‘, or “New Varak”, a monastery founded in northeastern Armenia by Prince Vassag of Norapert (Vassag Norapert’tsii) on the site of an older hermitage when the prior Luc (Ghougas), in possession of a piece of the Holy Sign, took refuge there in 1231. In the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, Varak monastery was an active scriptorium, and its abbots soon featured as bishops of the diocese of Van. Among them, Pierre (Bedros), in 1318 prevented the dispersal of the some 60 members of the community after the monastery was overrun by Mongols; during the reign of the archbishop John (Hovhannès), from 1421 to 1465, the famous doctor Markaré distinguished himself; in 1408-1409, alongside Thomas of Medzop‘ (T‘omas Medzop‘esti † 1447), he had attended the lectures of the theologian Gregory of Dat‘ev (Krikor Dat‘evasti) at Medzop‘ monastery (n° 9). In 1441, John took part in the election of Catholicos Guigaros I to the newly restored seat of Edchmiadzin (see n° 7), under the jurisdiction of which the monastery finally came at the turn of the 16th century, having left the Catholocossat of Aght‘amar (see n° 17). Varak at that time was considered the “Metropolis of the abbeys”; and the lower convent had already acquired two more churches.

While Varak was not spared by pillaging and destruction during the 16th-century Turkish-Persian wars, the scriptorium continued its activity; during this period, Zacharia of Varak (Zak‘aria Varaketsi), thought to be none other than the poet-bishop of Knounik‘, dedicated a song of praise to the convent: “ O that I may speak of Varak, desired place/ Beloved of all the angels/ Where the wood of the Cross of Christ/ Brought by the virgin Hripsimé…”. In 1559, under Abbot Nersès, Melik Ghulidjan finished restoring the upper convent and surrounded the lower convent with a wall; more work, financed by Baron Herabed, was done in the lower convent in 1591 under the archbishop and poet Stephen (Sdep‘annos): renovation of the churches, building of two narthexes, construction of new cells giving onto a long balustraded balcony. In the first quarter of the 17th century, under its abbot, the renowned Church Doctor Mardiros, the lower convent was already cited as one of the seven churches.

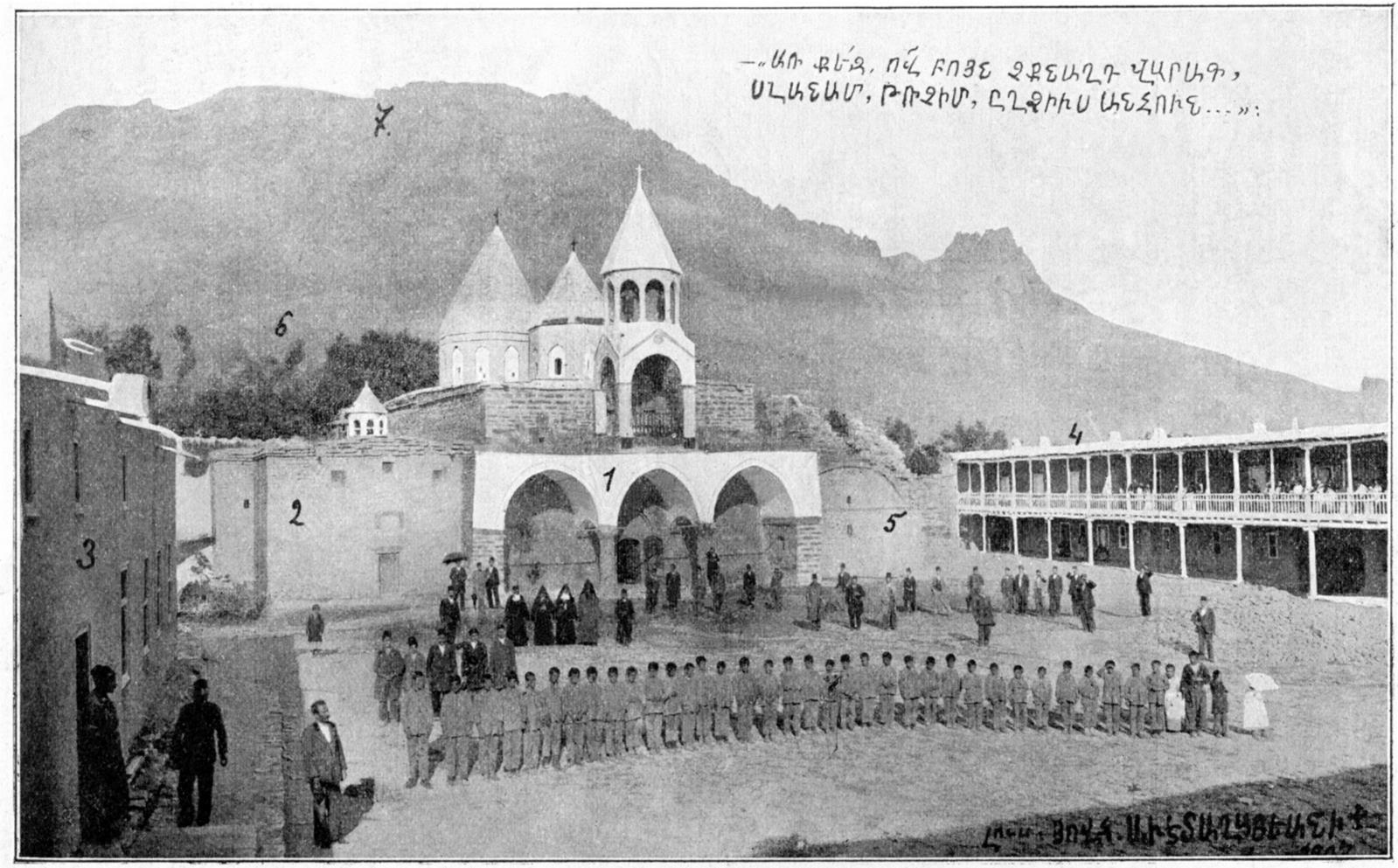

Pupils of the orphanage (Vasbouragan, 1930, 226).

The earthquake of 1648 severely damaged all of the buildings. Abbot Cyriaque of Avants (Guiragos Avantsetsi), who also had authority over the monastery of Saint Bartholomew (n° 34), immediately set about restoring the lower convent, whose churches, with the exception of Saint Sophia and Saint John, were renovated or rebuilt with the aid of the rich merchants Khodja Amirkhan, Khodja Tilantshi, Khodja Hovhannès and Markhas Tchalabi. To replace the collapsed buildings, he raised a large narthex in front of the church of the Mother of God, dedicated to Saint George and adorned it with wall paintings. In 1651, Varak was attacked by Suleyman Bey, the Kurdish lord of Khoshab [Hoşap], and his ally Tshomar, who made off with the treasure and all of the monastery’s movable properties. Ransom for the Holy Sign was paid by Markhas Tchalabi in 1655, and the relic was subsequently kept in the church of the Mother of the Lord at Van. The second half of the 17th century was marked by several attempts by the Catholicos of Aght‘amar to bring Varak back under their jurisdiction. The monastery subsequently went through a series of ups and downs. In 1668, the former patriarch of Constantinople (John V), archbishop John (Hovhannès T‘ut‘undji), served simultaneously as abbot of the monasteries of Varak, Salnabad and the convent of the Spirits (n° 31), before acceding to the seat of Aght‘amar as John II in 1669. In the same year, he renovated the monastery’s hydraulic network, damaged by a new earthquake. Abbot Garabed (1679-1697), who studied under Simeon P‘ok‘r, Simon the Younger, responsible for the restoration of the Holy Cross of Abarank‘ (n° 30), temporarily redressed the economic situation and house accounts, but this was only temporary. In 1715-1720, Varak was left empty for three years.

The revival of Varak was the work of Bartholomew of Shushants (Part‘oughimeos Shushantsi), disciple of Abbot Garabed, who re-established the community, opened the scriptorium and renovated the lower convent. The Saint George narthex bears an inscription dated 1724 ascribed to him. His successor John restored the lifestyle the monastery had enjoyed at the time of Garabed: it was a frequent stopover for Armenians, Kurds and Turks and regularly fed contingents of riders from the Ottoman garrisons of Van and Osdan [Gevaş]. During the epidemic in 1755, Abbot Gregory (Krikor Junjugants) moved the reliquary of the Holy Cross to the church of Saint Edchmiadzin in Van, probably the church of the Holy Sign, while in 1777, his successor archbishop Balthazar (Baldrassor), added a porch to the Saint George narthex. The following priors of Varak managed to keep up the lower convent, but not the upper one, which, after a series of depredations ceased to be permanently occupied. The priors also faced new difficulties: several were driven to resign and, in 1832, the Pasha of Van had Prior Mgrditch of Galatia (Mgrditch Kaghadiatsi) strangled. It was not until the election of Abbot Mgrditch Khrimian, who joined the Varak community in 1857, that the monastery gained renown among Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Mgrditch Khrimian, later elected abbot of the monastery of the Holy Precursor of Moush (n° 53) before becoming patriarch of Constantinople (1869-1873) and then Catholicos at Edchmiadzin (1892-1907), known by the people as “Little Father” (Hayrig), opened a seminary, later converted into a school of agriculture, a school and a printing shop, which published Ardziv Vasbouragani, “The Eagle of Vasbouragan”. The monastery also housed an orphanage, transferred to Van in the 1880s but laid waste during the 1896 massacres. During the Great War, during the Armenian Genocide, Varak was used as a temporary refuge for the surrounding population before being burned down by the Ottoman army.

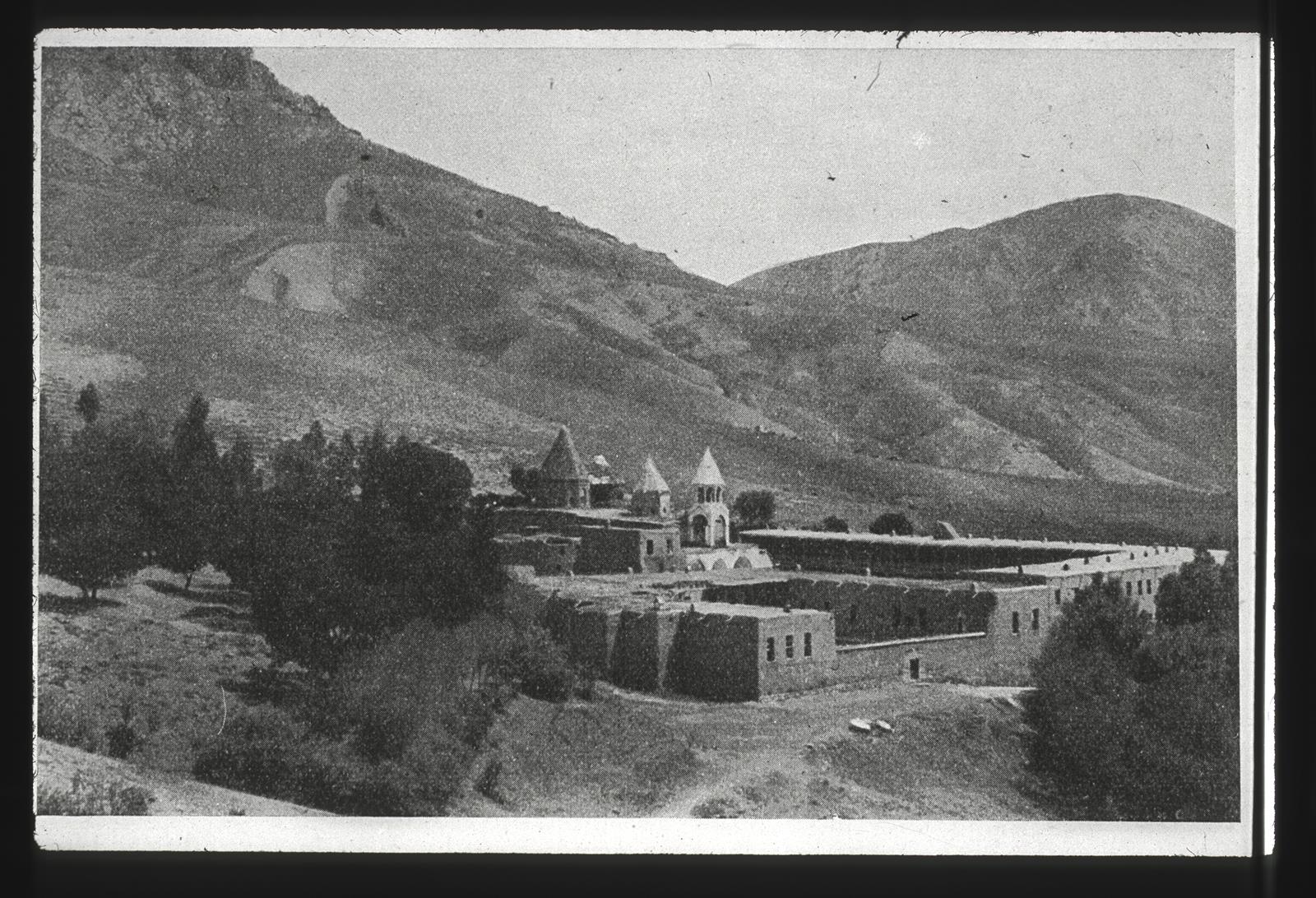

General view looking northwest, 1911 (Bachmann, Digitales Forschungsarchiv Byzanz, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Austria License. ).

The upper convent of the Varak monastery includes:

• The church of the Holy Mother of God, in the form of a cross with a dome, no doubt pre-dating the 11th century, restored in 1559 and in ruins since the 19th century;

• Adjoining the above on the north side, the church of the Holy Savior, a domed nave fallen into ruins at the same time;

• To the south of the preceding group, the chapel of Saint Gregory the Illuminator, in ruins;

• An enclosure and cells, in ruins;

• Near the pass separating the two summits of Mount Varak, at the foot of the rock known as Galileo (Kalilia), where the cross appeared lies the cave of the monks T‘otig and Hovel and their oratory;

• The Saint Stephen chapel, located lower down, close to the springs that provide water to the lower convent.

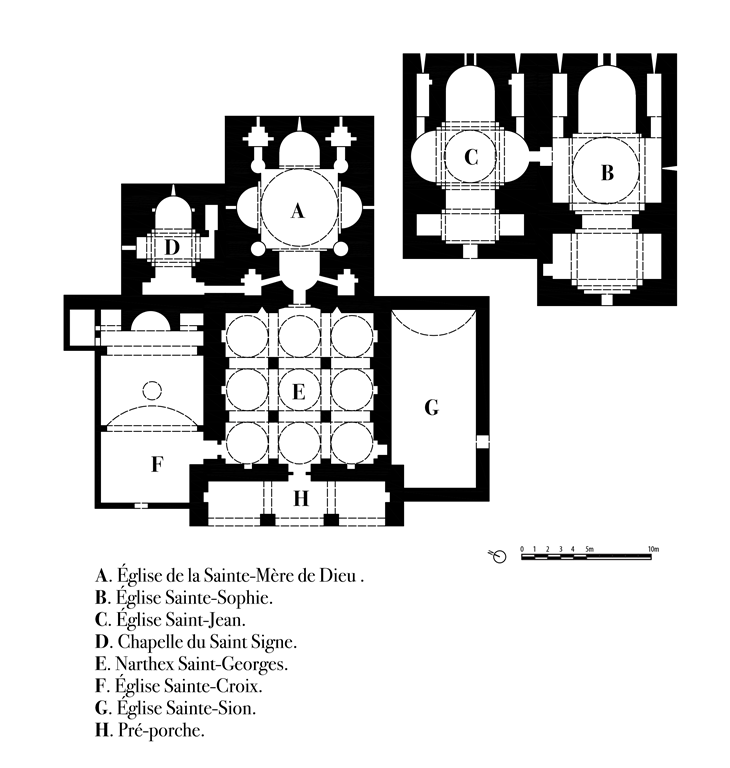

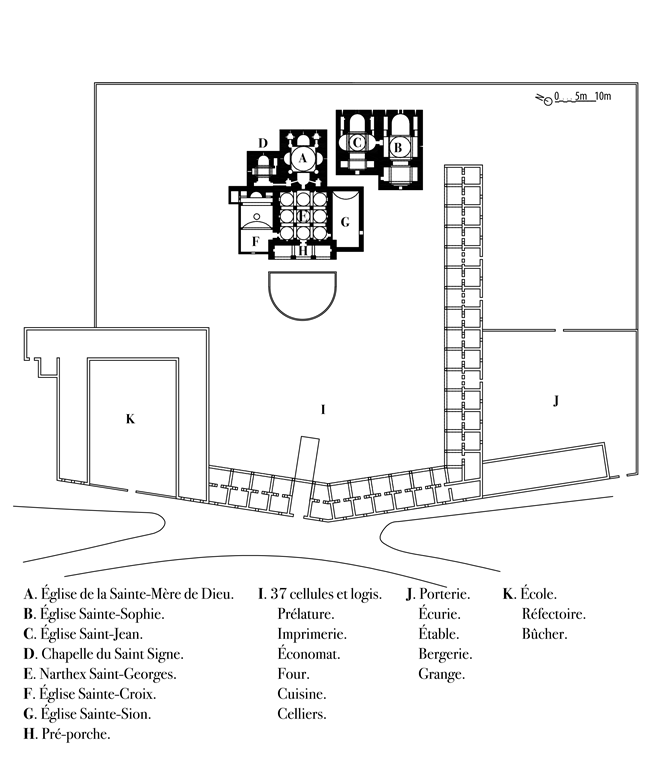

The lower convent contains:

Plan (Thierry, 1989, 136)

• The church of the Holy Mother of God (A), a tetraniche tetraconch measuring 19 × 10.6 m with four angle chambers, surmounted by a twelve-sided drum coiffed by a pyramid, perhaps restored or founded in 922 by Queen Mlk‘é – if this is not the primitive church of upper Varak – or by King Senek‘erim-John around the year 1000; restored and given a new drum after the 1648 earthquake; a cross-stone raised in 1301 by the monk Josaphat (Hovasap‘) used to be visible;

Holy Mother of God, interior, 2013 (Coll. Z. Sargsyan).

• The church of Saint Sophia (B), measuring 19 × 10.6 m, in the shape of an inscribed cross and surmounted by a dome, with narrow lateral chambers on either side of the apse, built by Queen Kushush in 981; unharmed by the 1648 earthquake, in 1846-1847 it had lost its drum and the western slope of the roof to a new quake; the church was called Pertov or Pertavor, “fortified”, because of the surface-mounted buttresses that had been added, in particular to the corners of the chevet before a wall was built around the lower convent.

• The church of Saint John (C), measuring 15.5 × 10.6 m, an inscribed triconch with narrow lateral chambers on either side of the apse, surmounted by a round drum with a conical dome, a short western nave with vaulted niches, built on the north side of Saint Sophia around the year 1000 as an extension of its chevet and communicating with the latter; together with Saint Sophia it makes up a separate complex from the other churches of the lower convent;

• The Holy Sign chapel (D), ribbed nave with a dome, originally 8 m wide and 10 to 12 m long; it was already counted among the “seven churches” in the early 17th century; abutting the north wall of the church of the Mother of God, its west end was shortened to accommodate the reconstruction program drawn up in 1648 and therefore communicates with this church; its stone dome collapsed and was rebuilt in wood;

• The Saint George narthex (E), a square building 14.5 m on a side with an octagonal drum coiffed by a pyramid rests on four central pillars and eight engaged piers or consoles adorned with paintings of prelates, angels and holy figures; built by the architect Diradur after the 1648 earthquake on the site of an earlier building and encroaching on the neighboring churches, consolidated in 1724, then enlarged no doubt in 1777 by a porch with three arches (H) surmounted by a rotunda bell tower; three tombs can be seen, in memory of King Senek‘erim-John, queen Kushush and Catholicos Peter I (Bedros Kedatartz, † 1058);

Narthex Saint-Georges, 2013 (Coll. H. H. Khatcherian).

• The church of the Holy Cross (F), a single ribbed nave with three apses, 16.5 m long and about 6.5 wide on the inside, erected in front of the Holy Sign chapel but bisected by the north wall of the Saint George narthex, with which it communicates; renovated in 1817 and given a turret; later made into a library and museum;

• The Holy Zion church (G), single nave 16 m long and approximately 6.5 m wide on the inside, renovated and deconsecrated in 1849 to be used as a granary;

• An enclosing wall, built in 1559, reworked in 1830 and augmented during the reign of Abbot Mgrditch Khrimian (I), lined on the south and southwest sides by two tiers of 37 cells and residential buildings some of which were built in 1591, the prelacy, printing shop, bursar’s office, oven, kitchen and cellars; the rest of the outbuildings: gate house, stables, sheep fold, barn, all distributed around the first courtyard (J); school, refectory, wood store grouped in the northwest corner around the second courtyard (K).

General plan : restitution

The jurisdiction of Varak encompassed 23 localities, including the Lim hermitage before the establishment of the abbatial seat of Lim and Gdouts (see n° 3). The monastery owned vast grazing lands and 619 arable plots. Varak’s dependencies included the Holy Mother of God priory at Ardjichag or Ardjag [Erçek], near the lake of the same name, east of Van. Provisionally separated at the time of Mgrditch Khrimian, the seats of Varak and the archdiocese of Van were reunited after his departure. The archdiocese counted 108 localities and 130 churches.

Laid waste by the army, the Varak monastery was confiscated after the Great War. Farmers took possession of what remained of the buildings, using them for their own purposes or for the stone. All of the outbuildings and the enclosure have disappeared. The churches of Saint Sophia and Saint John, still visible in the 1950s and badly damaged in the 1970s, have almost entirely disappeared: only the apse of Saint Sophia remains. The Holy Sign chapel, in the second complex, has also disappeared, while the churches of the Holy Cross and Holy Zion have been made into dwellings. The church of the Holy Mother of God has lost both its drum and its dome, as has the Saint George narthex, both being most often used as barns. All that remains to be seen on the inside are the paintings, and these too are damaged. The bell tower has been torn down but not the porch on which it rested. These vestiges, which are unprotected and in the midst of which other buildings have recently been erected, were further undermined by the earthquake in October 2011, in which the porch fell down. The ruins of the upper convent have completely collapsed.

In 2012 a journalist claimed that his family owned the site and that he was prepared to give it back to the Armenian people. However this opening has not yet been translated into actions.

Akinian, 1910, 47-50. Oskian, 1940-1947, I, 268-339. Oskian, 1953b, 208-214. Thierry, 1989, 132-149. Devgants, 1991, 267-277. Mirakhorian, 2013, 259-260, 305-307.