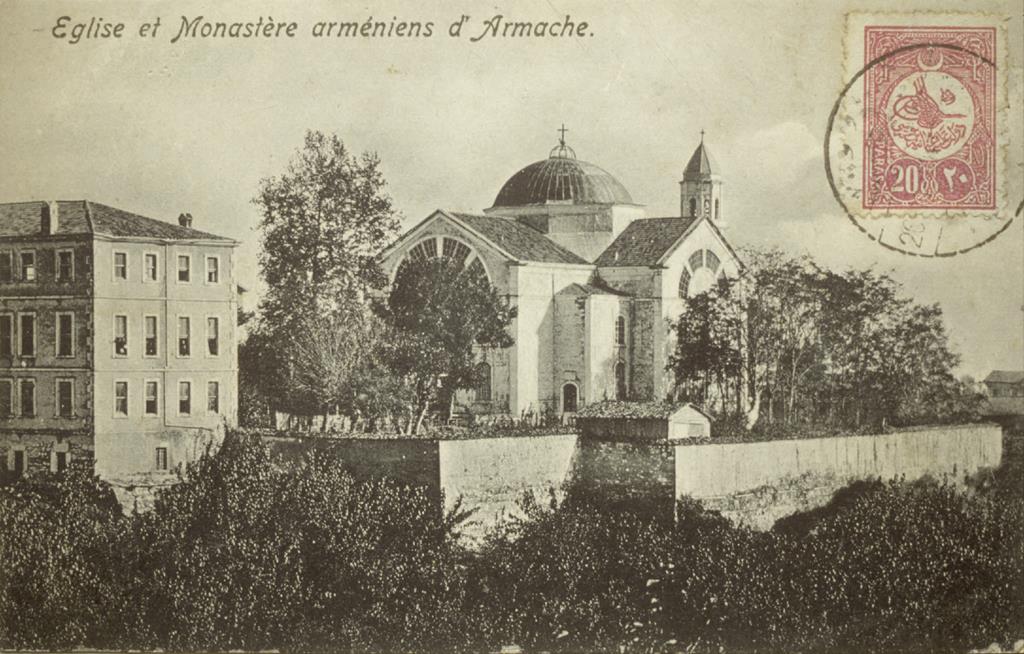

The Holy Mother of God monastery at Armash is located in western Asia Minor, 25 km northeast of Nicomedia [Izmit], at 40°50' N and 30°11' E. It was built on an outcrop, near the Armenian village of Armash [Akmeşe] and was surrounded by fine gardens.

Although there had been an Armenian presence in Armash in the 15th century, it is commonly accepted that the population of the village was made up essentially of descendants of the many eastern Armenians that had arrived in the region of Nicomedia and Bursa [Bursa] at the time of the Turco-Persian wars in the 16th-17th centuries, and in particular in 1608. This increase in the Armenian population, as well as the resulting economic surge, required the establishment of a local spiritual center and pilgrimage site: this would be the Armash monastery.

Vue générale du monastère d'Armache. (CPA coll. privée).

By his own account the monastery was founded in 1611 by the Doctor and annalist Gregory of Taranghi or Gamakh [Kemah] (Krikor Taranaghtsi or Gamakhetsi, 1576-1643), who earlier had co-founded the Armenian Church of Rodost‘o [Tekirdağ], in Thrace. In other sources the same initiative is attributed to Bishop Thadeus (T‘atéos), the first bishop of the diocese of Armash, which had jurisdiction over the churches of many of the surrounding localities: Geyve, Bazar [Pazar], Sölöz, Gürle, Bandırma, Balıkeser [Balıkesir], Kirmasti [Mustafakemalpaşa] and Biğa [Biga]. In 1786, though, a new period began for Armash with the establishment of a religious congregation and a school by Archbishop Part‘ughimeos Gabudiguian. But it was not until the 1860s that the monastery began to play the fundamental role it would continue to have for the Armenians of Turkey until the outbreak of the Great War. In 1864 the establishment opened a printing shop and published the journal Huys, “Hope”. In 1866, the Armash monastery broke away from the diocese of Nicomedia, to which it had been attached, and became an autonomous abbey. The principal architect of this change, Father Kevork Aliksanian, became archbishop of Armash in 1869. In 1872 he completed the construction of a new church, begun in 1866. His successor, Khoren Ashëkian (1872-1888), founded a boarding school at the monastery, Ghevontiants School. The school’s success, the development of the printing works equipped with new machines from Europe, and the intellectual potential concentrated in the monastery made these years a promising period. The aftermath of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878 was nevertheless a disaster for Armash: in particular, the school was closed and publication of Huys stopped.

Fête de la Sainte-Croix, présidée par le patriarche Eghiché Tourian (BNu).

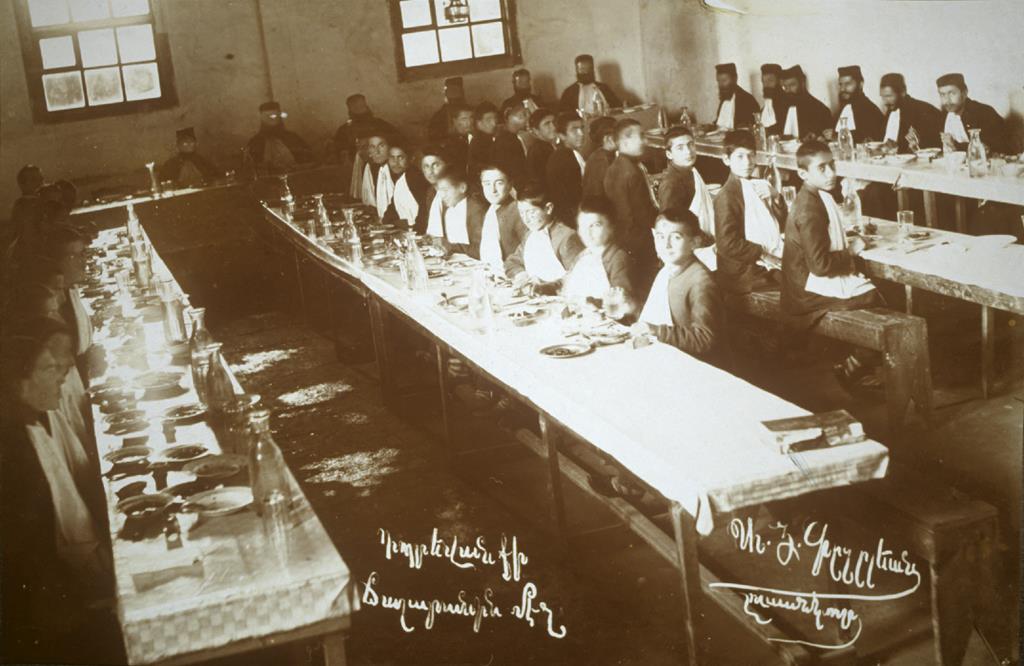

Despite serious difficulties and modest means, Archbishop Khoren Ashekian, managed to turn the monastery around, re-open the school and lead Armash to its apogee. But, on 27 September 1888, a major fire destroyed a significant part of the village as well as the south wing of the monastery, which housed the school. The accession of Mgr. Khoren Ashekian to the patriarchate (as Khoren I, 1888-1894) immediately afterwards enabled the damage to be repaired rapidly, though. Because the Armash monastery had been directly attached to the patriarchate since 1866, Patriarch Khoren was able to fulfill his ambition to make it a major intellectual center, a “Venice of the Armenians in Turkey”, referring to the role this town had played since the 16th century in the development of Armenian printing and letters in Europe. In the 19th century, particularly with the promulgation of the Armenian National Constitution in 1863, the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople became a central institution in the religious, political and cultural life of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire. It was therefore indispensable to open a modern seminary for training future religious and intellectual leaders of the Armenian nation living in the Empire. And so in 1889 the great seminary of the Armenian patriarchate of Constantinople was inaugurated in Armash.

Replacing Patriarch Khoren at the head of the monastery, Archbishop Maghakia Ormanian undertook major work there: he erected a large building to house the seminary, whose direction was entrusted to Father Eghiché Turian; and he constructed several outbuildings, opened a silkworm-breeding station, planted mulberry groves and installed a watermill. His seven years of service (1889-1896) were the highpoint in the life of this institution. The massacres of 1895 temporarily put a damper on this dynamic: Ormanian and Turian, as well as many teachers and students were forced to leave Armash, where the interim was ensured by Father Nerses Der Partughimeossian. During this time of tension and insecurity, pilgrimages became more difficult and infrequent. With Ormanian’s election to the patriarchate in 1896, however, Armash monastery was granted a monthly patriarchal subsidy, which enabled it gradually to resume its activity. Now archbishop, Eghiché Turian – later to become patriarch of Constantinople in 1909 and of Jerusalem in 1921 – became superior of the monastery in 1898, a post that would be held from 1904 to 1907 by Father T‘orkom Kushaguian, who would succeed Mgr. Turian in 1929 as patriarch of Jerusalem. The upheavals accompanying the Young Turks’ revolution in 1908 affected Armash as well, causing a sudden slowdown in its activity. It fell to Father Papguen Gulesserian, future coadjutor of the catholicos of the House of Cilicia, Sahag II (see n° 73), to stabilize the situation and to breathe new life into the institution. His work would be continued until 1915 by Father Mesrob Naroyan.

Mosquée édifiée à l’emplacement du bâtiment du séminaire et fontaine, 2011 (Coll. Zakarya Mildanoğlu).

The teaching staff and students of Armash played a considerable role in the intellectual and religious life of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire, providing the Armenian people of Turkey with a large number of devoted churchmen and administrators. With the foundation of a new library in 1889, Armash also became a first-rate cultural center. In 1904, the library held 223 old manuscripts, a number that had already doubled by 1914. The Armenian genocide in 1915 not only resulted in the deportation of the entire Armash congregation but occasioned the destruction of the inestimable riches assembled there.

The Armash monastery included:

• The Holy Mother of God church, founded in 1611, renovated in 1720, then at the end of the 1790s and again in 1820 after having been ransacked in 1804 by bands of looters. The church was entirely rebuilt between 1866 and 1872, while its roof was restored in 1908-1909. A bell tower with rotunda had been added in 1892 at the southeast corner. An Italian portrait of the Holy Virgin could be admired there.

• The seminary building, constructed in 1889 on the site of an earlier school founded in 1786.

• The hostelry, a vast building with 40 accommodations, erected in 1890 on the site of older buildings destroyed by fire in 1888.

• A watermill – known as the Unjian mill, from the name of the Unjian brothers, Apig and Mat‘us, benefactors of Armash – installed in the 1890s and equipped in 1911 and 1913 with a modern machinery.

Le moulin du monastère (BNu).

• A sericulture shop installed in a building raised in 1892.

• A combination library-museum, built in 1911 to house the monastery’s valuable collections.

• A fountain, built in 1827.

• Agricultural facilities and a vegetable garden reconfigured in 1910.

• Mulberry groves.

• A farm built in 1863, with access facilitated by a new wooden bridge built in 1912.

Séminaristes dans le réfectoire (BNu).

A major pilgrimage site, Armash drew the faithful from much further abroad than simply the region of Nicomedia. Pilgrims came from Iconium [Konya], Smyrnia [Izmir], Kütahya, Brusa, [Bursa]; from Constantinople [Istanbul], Andrinople [Edirne], and even from Philippopolis/Plovdiv, in Bulgaria.

The Armash monastery was plundered in 1915, then confiscated after the Great War and left to the devices of all comers. Destruction of the church and adjoining buildings began upon the occupation of the site by the Kemalists in 1923-1924; part of the remaining walls were used to build a first mosque in its place, which was replaced in 1994 by a new and larger edifice. The seminary building was still standing in the 1990s. But, damaged by the 1999 earthquake, it was demolished the same year. Standing empty and in ruins, a small portion of the outbuildings, housing in particular the old printing works, was still visible in 2011. It had long been used to store unwanted items. At the same date the fountain and, further on, the abandoned mill house could also still be seen.

Épriguian, 1903-1905, I, 313-315. Armache, 1914, passim. Minasyan, 2000, 32-39. Özkan, 2000, 32-35.