In the southeast corner of Lake Van (Pznunik‘ sea, Pznuniats dzov), at 38° 20’ N and 43° 02’ E, on an island of the same name, lies the monastery of the Holy Cross of Aght‘amar [Akdamar], an important scriptorium and a catholicosate since 1113. The church of the Holy Cross around which the monastery rose is one of the most famous Armenian monuments in Turkey, as well as one of the most original, for both its architecture and its decoration; above all this church is surrounded by a long, prestigious history.

Aght‘amar was already mentioned in ancient times. At the time of King Diran (=Tiran, 340-350) it housed a fortress belonging to the dynastes of Rëshdunik‘, a mountainous region extending south from Lake Van. Like the other islands in this lake, Aght‘amar acquired a hermitage at an early date. When the Ardzrunid king of Vasbouragan, Kakig (= Gaguik, 908-943), decided to take up residence there, he transferred Aght‘amar’s prior, Elijah (Eghia), to the new convent of Illi [Dağyöre]. On the island, the King established a fortified city in the middle of which he built his palace and, alongside the palace, a church: the Holy Cross. The architect, Manuel, who certainly drew his inspiration from Aghpag’s Holy Cross church (n° 33) built a century earlier on Ardzrunid lands, carried out the work between 915 and 921. The new church was richly decorated with high reliefs on the outside and frescos in the interior. In all likelihood, it became the seat of a metropolitan that Kakig had appointed for his kingdom in the person of his nephew, Elisha (Eghissé).

Interior of the church of the Holy Cross: royal balcony of the Ardzrunids (Bachmann, 1913, n° 32).

When the kingdom of Vasbouragan was ceded to Byzantium and King Senekerim-John (Senek‘erim-Hovhannes) was installed at Sebaste [Sivas] in 1021, the Ardzrunid, Khedeneg I, master of the Amuig fortress [Yeşil Yurt / Özyurt], on the east shore of the lake opposite the island of Lim, occupied Aght‘amar. His descendants would retain their hold on his domains. Among these descendants was David (Tavit‘), archbishop of Aght‘amar at the start of the 12th century. In 1106 he took in Catholicos Basil I (Parsegh), who had fled Ani with the sacred attributes of his office, among which was the right hand of Saint Gregory the Illuminator. In 1112, after Basil I had left Aght‘amar for Euphratesia and the region of Cilicia and was about to die after having made his young nephew catholicos, David, who had retained possession of the right hand, proclaimed himself catholicos instead, thus inaugurating in Aght‘amar a long line of dignitaries who would hold the title until the 20th century. Anathematized by the synod of 1114, the new see nevertheless managed to resist and even extend its jurisdiction beyond Vasbouragan.

From the pontificate of David I († before 1165) until the start of the 17th century, all occupants of the see of Aght‘amar seem to have belonged to the Ardzrunid royal lineage. While Amuig was lost before the end of the 12th century, the island of Aght‘amar remained in their possession, although in the first quarter of the 13th century it passed to another branch of the Ardzrunids, that of Ark‘ayun Sefedin. Catholicos Stephen III (Sdep‘anos, 1272-1296), who restored the dome of the Holy Cross and built the church of Saint Stephen nearby in 1293, was his son. Brother of the former, Zacharia I (1296-1336) would build Lim’s church of Saint George (n° 3). In Aght‘amar, where the palace of Kakig I had perhaps already been destroyed, Stephen built a winter residence near the church of the Holy Cross curch and to the east, a summer residence. We are also indebted to him for the chapel of Saint Sergius, built at the northeast corner of the church of the Holy Cross. Above all, when the Mongolian Ilkhanate embraced Islam and persecution of the Christians intensified after the death of Abu-Saïd Bahadur (1336), Stephen negotiated a relaxation of the conditions imposed on his Church. At the time, Aght‘amar was a working scriptorium. There in 1303 Daniel of Aght‘amar (Taniel Aght‘amartsi) copied the sole manuscript extant today of the famous History of the House of the Ardzrunids, written at the start of the 10th century by Thomas Ardzruni and continued by several anonymous hands. Under Zacharia of Aght‘amar (Zak‘aria Aght‘amartsi), the art of illumination flourished. Under Stephen III (1336-1346), the see of Aght‘amar had 14 bishoprics. In 1371, under Catholicos Zacharia II, who was martyred in 1393, some fifteen members of the clergy served the church of the Holy Cross.

The catholicosate of David III (1393-1433) was contemporaneous with Tamerlane’s campaigns – Van was massacred in 1387 –, and then with the rise of the Black Sheep Turkmen and the new ravages occasioned by their wars with the Timurids. There were also several Kurdish seigneuries within the jurisdiction of Aght‘amar. The island was occupied in 1428, and then again from 1431 to 1433. In 1441, under Zacharia III the Great (1434-1464), who unquestionably played a political role with the Turkmen DJihan Shah, the Armenian catholicosate was transferred to Vagharshabad (Edchmiadzin), an undertaking to which Thomas Medzop‘ (T‘ovmas Medzop‘etsi, † 1447, see n° 9), in particular, devoted his efforts. The initiative was rejected by the incummbent catholicos in Cilicia, who refused to leave Sis [Kozan], and ended with the election of a new catholicos at Vagharshabad (see n° 7), without considering the see of Aght‘amar. To be sure, the anathema against Aght‘amar was lifted at the same time, but it also prompted the attachment of the bishopric of K‘adshperunik‘ to the new see, which now extended to the regions of Arjesh [Erciş] and Ardzgué [Adilcevaz] north of Lake Van. The stakes entailed and the rivalries they prompted led Zacharia III to appropriate the right hand of the Illuminator and, with the support of Jihan Shah, to unite the sees of Aght‘amar and Edchmiadzin in 1460 under his own authority.The previous year he had already foiled a Kurdish attempt to invade the island.

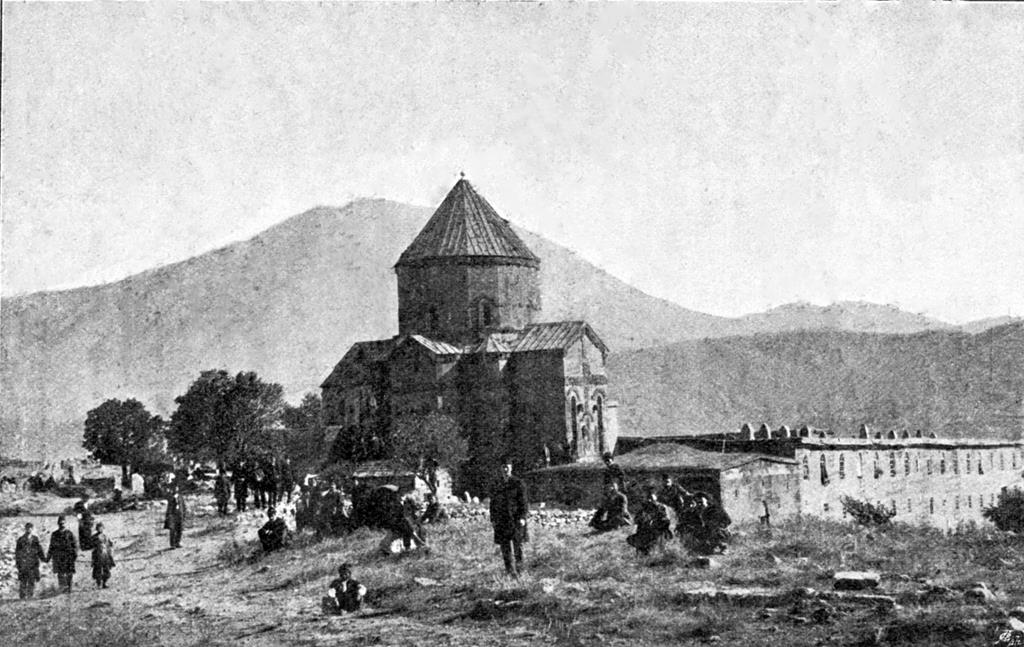

General view of the northwest side of the church and catholicosate (Araks, 1898, 83).

Zacharia III was poisoned to death in 1464, but his political strategy was continued by his successor and nephew, Stephen IV (1465-1489). On his accession to the title of catholicos, he crowned his half-brother, Sempad, king and, in 1467, once again won the see of Edchmiadzin. But the death of Jihan Shah the same year put a halt to the great plan to restore the Ardzrunids under the banner of the Black Sheep. The pontificates of Zacharia III and of Stephen IV, which occupied over half of the 15th century, were nevertheless a prosperous time for Aght‘amar and its school, which boasted a succession of talented copyists and illuminators: Thomas the Hermit (T‘ovma Miaguiats), already active at the beginning of the century; his pupil the “great philosopher” and chronicler Thomas Minassents (T‘ovma), who was none other than the maternal uncle of Stephen IV; the monk Hayrabed, pupil of Thomas; as well as Archbishop Nerses, brother of Stephen IV. In 1470 the Aght‘amar community numbered some one hundred monks living in the midst of a well-populated, fortified town.

Significantly, King Sempad’s son would not become king but catholicos, taking the name of Zacharia IV (1489-1496). The catholicos and poet Gregory I of Aght‘amar (Krikoris Aght‘amartsi, 1512-1544), whose allegorical plays were long copied into song collections, was Zacharia’s grandson. Gregory III (1586?-1608) restored the winter and summer residences, the church of Saint Stephen and the drum of the Holy Cross, and gave the latter a narthex. He defended the primacy of Aght‘amar against Edchmiadzin – a colophon titles him Catholicos of All Armenians – while several bishoprics, among which Varak (n° 1), which includes Van, had already been removed from his jurisdiction. After Stephen V (1608-post 1648), it seems that the see of Aght‘amar was no longer in the Ardzrunid line. With the consolidation of the Ottoman Empire, they would seek to ensure themselves against the growing power of Edchmiadzin – now in Persian territory – which asserted itself as the catholicosate of “All Armenians”, a status that continued also to be claimed by those catholicos who had remained in Sis, in Cilicia, after the transfer in 1441. Between 1650 and 1750, this rivalry translated into a conflict over jurisdiction and pre-eminence that became particularly acute under Mardiros I (1660-1662) and Nicolas I (Nigoghayos, 1736-1751). The territorial aspect of the conflict concerned not only Varak-Van but also other southern dioceses, like Paghesh [Bitlis ], Moush [Muş] or Amida (Dikranaguerd [Diyarbakır]). Finally in 1669 it was Archbishop John (Hovhannes Tutundji), abbot of Varak (see n° 1 and 31), who became catholicos at Aght‘amar as Jean II.

The first major concession to Edchmiadzin came from Thomas I, who had himself crowned in 1683 by Eliazar I of Aïntab [Antep] (Eghiazar Aynt‘abtsi, 1682-1691). Thomas was a doctor from the Tshënk‘ushe [Çüngüş] (n° 79) school who became patriarch of Jerusalem (1666-1682) and won the see of Edchmiadzin on the wave of a large consensus; but the restrictions imposed subsequently on Aght‘amar’s prerogatives prompted him to reverse this opening. The conflict then shifted to the ordination of future catholicos of Aght‘amar at Edchmiadzin or the confirmation of the holders of the seat of Aght‘amar by the Edchmiadzin catholicos. In parallel the clash also focused on the appointment of bishops and the privilege of preparing the Holy Oil of Chrism. The successor to Nicholas I, who finally capitulated, was Thomas II (1761-1783), the last of the Ardzrunids at Aght‘amar; he was confirmed by Edchmiadzin, whose authority would nevertheless continue to be contested. The catholicos of Aght‘amar would have to face other difficulties as well: in 1823, Harut‘iun I of Ardonk‘ (Harut‘iun Ardonetsi) was assassinated by a Kurdish bey in the Holy Cross monastery at Khizan (n° 25). Throughout this period, nevertheless, considerable work was being carried out at Aght‘amar: the monastery wall was restored in 1671; a baldaquin was erected over the altar in the church of the Holy Cross in 1756; a new narthex was constructed in 1763 in front of the church of the Holy Cross, and the same year a vast monastic building was put up to the south, replacing the former winter and summer residences. A bell tower was added to the south conch of the same church in 1790. In 1803, the Saint Sergius chapel received a narthex abutting the north conch of the church of the Holy Cross. In 1824, at the request of Catholicos John V of Shadakh [Çatak] (Hovhannes Shadakhetsi), Ghazar Khalipian set about reconstructing from the beginning the list of all the catholicos of Aght‘amar, deliberately taking back his list to 921, that is to King Kakig I and his nephew Elisha.

With the onset of the Reforms, the catholicosate of Aght‘amar was placed under the authority of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople and of the religious and civil authorities that thereafter governed the affairs of the Armenian nation in the Ottoman Empire, a new situation that was to foment tension and violence. The patriarch of Constantinople opposed maintaining the see of Aght‘amar and, in 1844, exiled the new catholicos, Khachadur II of Mogs, (Kachadur Mogatsi, 1844-1851). Once reinstated, he would have the greatest difficulty exercising his ministry, as would his successors. In a tense climate marked by the assassination of his predecessor, Kachadur III Shiroyan (1864-1895) managed to become catholicos and consolidate his authority, though not without having waited until 1875 for the authorities in Constantinople to lift the charges they had initially brought against him. This active catholicos reorganized the seminary on the island of Aght‘amar and built up a library of manuscripts housed in a new residential building (1884). He also undertook the restoration of several churches and monasteries, among which that of Saint George of the Mountain (n° 28), and endowed the Akhavank‘ house, outside the walls on the opposite shore, with a new residence and a school. At his death, he was succeeded by Father Arsen Markarian as locum tenens. The catholicosate then passed under the provisional administration of a managing council appointed by the patriarchate of Constantinople.

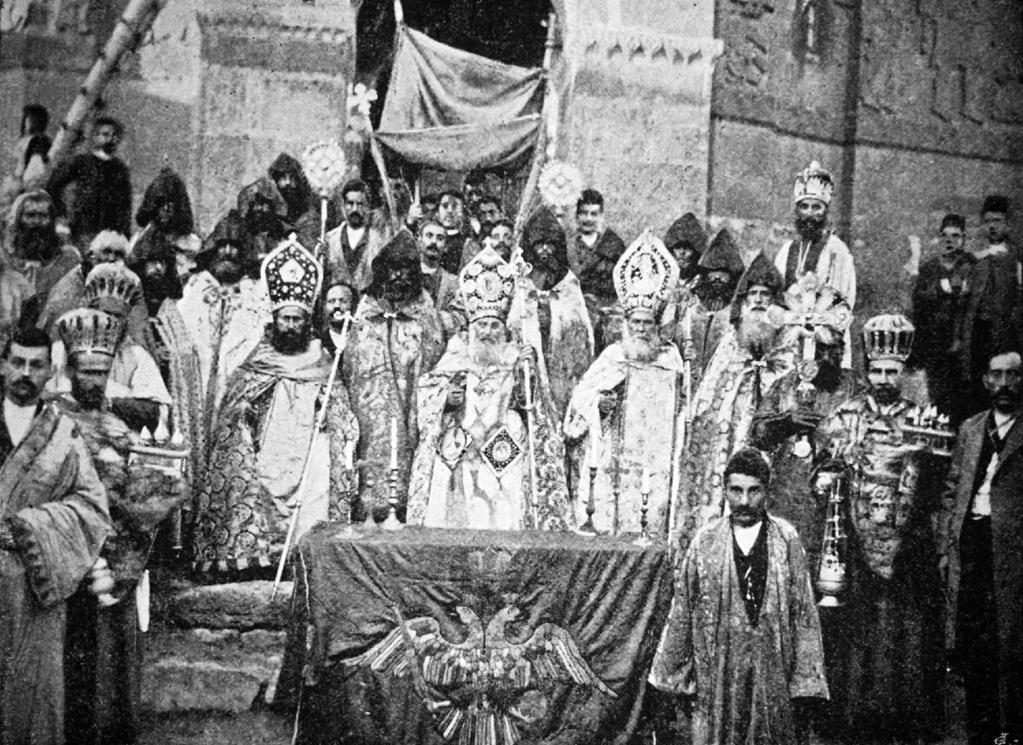

Khachverats ceremony (Araks, 1894-1895, fasc.2, 56).

The Holy Cross monastery of Aght‘amar includes:

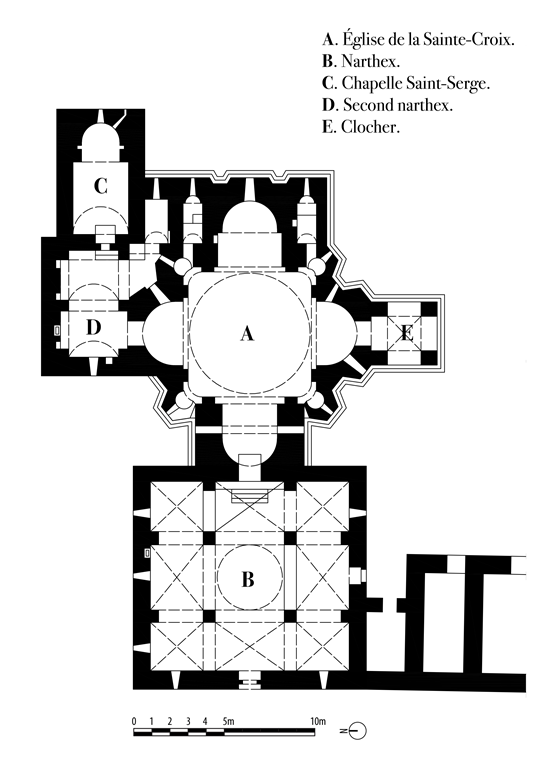

Plan (after Bachmann)

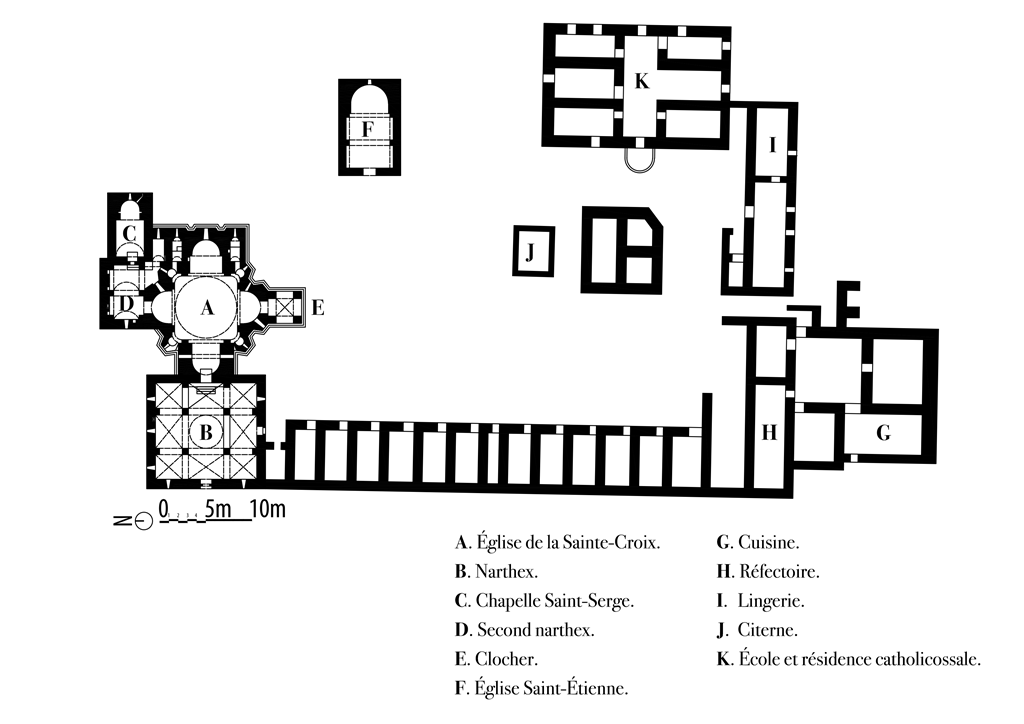

• The church of the Holy Cross (A), a tetraniche tetraconch measuring 16.1 x 13 m with two lateral chambers on the west side, a sixteen-sided drum and dome with a pyramidal roof, built in 915-921. The dome was reconstructed in 1293 and then restored in 1556 and 1602. The south conch has a tribune with balustrade, originally accessed from the royal palace by way of a double outside staircase. This was removed in 1790 to allow the construction of a bell tower (E) with a rotunda. The church interior was entirely covered in frescos – partially preserved – representing, on the dome and drum, the Creation and the Original Sin, and on the other walls, Christ and numerous Gospel scenes, from the Annunciation to the Second Coming. The outside of the church is heavily decorated with high-relief sculptures arranged in three tiers, featuring a succession of Old Testament episodes and figures, Saints, vine tendrils, fruits, fabulous creatures and all kinds of animals. On the west façade, King Kakig is shown offering his church to Christ.

• A narthex (B) measuring 11.8 m from east to west and 13 m in width, built in 1763 at the western entrance to the church; it has four central columns delimiting in the center a compartment covered by a calotte and surrounded by eight other compartments covered with herring-bone vaulting.

• The chapel of Saint Sergius (C), a small single-vessel nave measuring 6.2 x 4.6 m, built at the beginning of the 14th century near the northeast corner of the church of the Holy Cross.

• A second narthex (D), built in 1803 against the north wall of the church of the Holy Cross and communicating with it through the north conch, extends the Saint Sergius chapel 7.5 m to the west.

• The church of Saint Stephen (F) , a single-vessel nave with transverse arches some 11m long and 6.8 m wide, built in 1293 southeast of the church of the Holy Cross and restored in 1602. At the beginning of the 20th century the western part of the nave had collapsed.

• The monastery buildings laid out to the south around a courtyard: cells aligned on two levels, restored in 1873; kitchen (G), refectory (H), laundry room (I), cistern (J), school and residence of the catholicos (K), built in 1884.

• A cemetery for the monks and catholicos, east of the church of the Holy Cross;

• The Saint George chapel located in the southeast part of the island.

• Near the Saint George chapel, the Red chapel or the chapel of the Holy Mother of God.

• On a small island extending the southwest tip of the main island, the oratory said to be that of Queen T‘amar, a small single-vessel nave with a saddleback roof traditionally dated to the reign of Kakig I.

Plan général du monastère (d’après Bachmann)

The Holy Cross monastery at Aght‘amar possessed plow lands and grazing lands. It also had a house outside the walls, on the lakeshore: Akhavank‘. At the beginning of the 20th century, the jurisdiction of the catholicosate of Aght‘amar covered two large dioceses south of Lake Van: Aght‘amar and Khizan, which in 1910 possessed a total of 272 churches in 194 sites. Forty monasteries were under the jurisdiction of the see of Aght‘amar.

Plundered in 1915, the monastery of the Holy Cross at Aght‘amar was confiscated after the Great War and left empty. Sometime around 1950, the State undertook its demolition. This exceptional monument of art and architecture was saved in 1951 thanks to the intervention of the writer and journalist Yaşar Kemal. Nevertheless, the site continued to suffer. In 2005, the Turkish minister of Culture finally decided to restore Aght‘amar. The work was completed in the fall of 2006, and the restored monastery was inaugurated in March 2007 in a ceremony whose political significance, like that of the restoration, was the subject of much commentary. On 19 December 2010, Archbishop Aram Ateshian, representing the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, was able to celebrate mass for the first time since 1917. Nevertheless the monument has been listed as a museum.

General view from northwest, 2012 (Coll. Zaven Sargsyan).

Although the restoration of the church of the Holy Cross of Aght‘amar resorted at times to ill-suited solutions, and therefore did not scrupulously respect the rules that should guide any work on a historical monument, it has protected the Holy Cross and its buildings from the elements. The restoration has also made it possible to prevent the definitive destruction of the remaining frescoes, particularly targeted by malicious acts. Saint Sergius and its narthex have been given rough saddleback roofs, and the church of Saint Stephen is not finished. Since all the monastic buildings have been destroyed, the ground plan has been partly reconstructed by excavating the base of the walls. Behind the complex, the cemetery had already been largely disrupted and many cross-stones broken. The Red chapel and the Saint George chapel have disappeared, and Queen T‘amar’s chapel, still visible in the 1960s, now lies in ruins. For a long time, all that has remained of the courtyard are a few sections of wall.

Akinian, 1920, passim. Oskian, 1940-1947, I, 86-133. Kurdian, 1951,112-113.Khatchikian, 1955-1967, ii [1958], 117-118.Hakobian, H., 1976, 67-118. Thierry, 1989, 269-291. Devgants, 1991, 169-176.

SaveSave

SaveSave